In a cavernous plant on the outskirts of Coventry, a massive bet is being placed about the sort of vehicles that will be trundling around cities and along motorways over the next 30 years. The factory is the result of a £325m investment by a big Chinese automotive group and adds up to one of the boldest efforts in the UK to create a new generation of electric cars.

The site is run by London Electric Vehicle Company, a UK-based company owned by Geely, a fast expanding group controlled by the leading Chinese entrepreneur Li Shufu – who is known for his spare-time hobby writing poetry, as well as for a relentlessly global approach.

A key part of Li’s plans for LEVC is to make the Coventry plant a centre for development of new types of electric car, aided by recruitment of technical specialists, many of whom are likely to start at LEVC either as apprentices or engineering graduates.

That makes the factory a prominent showcase for novel engineering and manufacturing ideas of the sort Made Here Now wants to highlight as part of the effort to encourage more young people to consider UK production for a career.

The Chinese investment in Coventry stands out against the decision by Sir James Dyson one of Britain’s best known entrepreneurs to spurn the idea of starting an electric car plant in the UK, choosing Singapore instead.

Among the 750 employees at the site – which opened in 2017 – is Pauline Dumont, one of the factory’s 200 development engineers. The 26-year-old Belgian joined LEVC in 2015 after finishing a postgraduate degree in automotive engineering at Cranfield University.

“I was excited at coming to work here – the job gives me the chance to help create a completely new product starting from zero,” says Dumont.

“It’s been great being part of a team doing something special. I feel I have learned a massive amount in a short time.”

Dumont is among about 30 graduate engineers that LEVC has employed, along with a similar number of manufacturing apprentices, since Geely unveiled its plans for the company around 2015.

.JPG) Pauline Dumont is playing a key role in engineering developments behind the new London taxi

Pauline Dumont is playing a key role in engineering developments behind the new London taxi

This was two years after Geely bought Manganese Bronze, a venerable Coventry-based automotive business that had made London’s taxis for decades, after it collapsed into administration

The first products from the factory are a new series of electric black cabs for London, which in time will replace the diesel-powered taxis that form a big part of the London street scene, but which will be gradually replaced by less environmentally intrusive new models. The LEVC-produced vehicle has been expressly designed to fit in with the capital’s increasingly onerous clean-air regulations.

Diesel vehicles are regarded particularly negatively because of their strong association with pollution and widespread health problems. Over the next decade, it appears that, worldwide, increasing numbers of vehicles will be based around electric propulsion instead of petrol and diesel engines — Britain and France have already said that new cars sold in their countries must be fully electric by 2040.

Volvo, the Swedish company that Geely bought in 2010 as part of a big international push, says that from 2019, it will no longer launch models powered only by internal combustion engines and all its vehicles will be hybrid or electric.

As for Geely’s efforts in the UK, it formed a joint venture with Manganese Bronze in 2007, and took a 20 per cent stake in the business. After the full acquisition and the development of its electric propulsion plans, Geely renamed the business LEVC.

Pointedly it dropped any references to taxis in the title, signalling its ambitions. Geely plans to ramp up production from Coventry to 20,000 vehicles a year by 2020. The output will comprise not just taxis but other sorts of electric cars aimed at markets outside Britain.

Steve Fitter, assembly manager at the Coventry factory, who started at Manganese Bronze in 2000, says the Chinese investment has been “hugely welcome”. The Chinese owners have, he says, “a broader view of the world” than the previous top management at Manganese Bronze.

Veteran factory manager Steve Fitter says the Chinese investment has widened the company’s horizons

Veteran factory manager Steve Fitter says the Chinese investment has widened the company’s horizons

Alluding to the graduate engineers and apprentices at the factory, Fitter says: “We want to embed them into the company’s development programme. We want to grow a new workforce that will create a product cycle of new vehicles.”

The initial product from the factory – the London taxi - is strictly speaking a hybrid as it combines a lithium-ion battery with a petrol engine. That gives the vehicle the ability to travel for about 70 miles purely under electric power, or a total of about 370 miles when in hybrid mode and fuelled also by petrol.

Among the novel techniques being pioneered at the plant is extensive use of plastic- based composite panels that feature in much of the vehicle’s body, in place of the more orthodox steel. The panels are fixed to the car’s frame – made from aluminium, again rather than steel – through glueing rather than the normal welding process. Basing the structure of the car on plastics and aluminium leads to a less weighty body, offsetting the effect of the heavy battery, helping to reduce energy use when on the road.

A key partner in this part of the development is Novelis, the US-based aluminium producer owned by the Indian industrial group Hindalco. Novelis has a partnership with LEVC under which it supplies the aluminium in the body from a plant in Germany. Steve Fisher, chief executive of Novelis, told Made Here Now the relationship had led to some “unique insights” for both companies that could help with the development of more vehicle models in the future with similar characteristics.

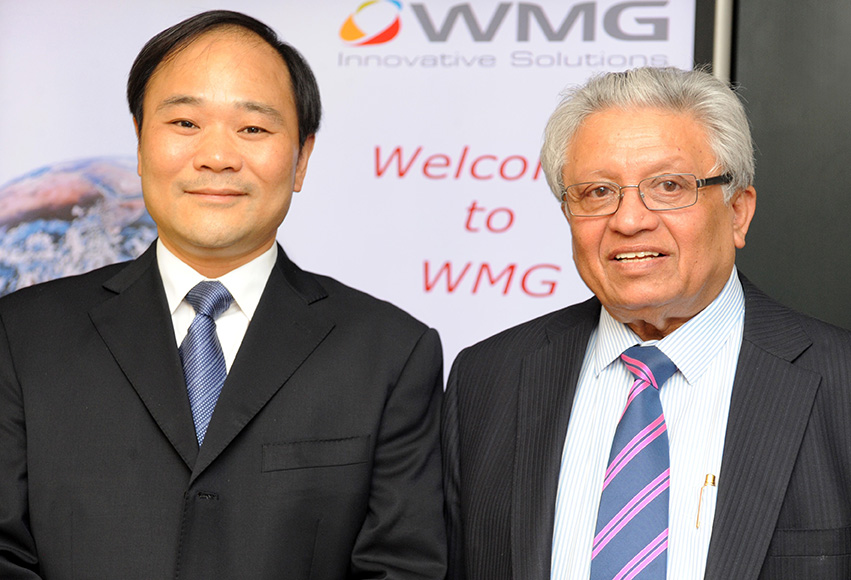

Watching from the sidelines as the Geely plans for Coventry have taken shape is Lord Kumar Bhattacharyya, doyen of the UK manufacturing scene who is the chairman and founder of Warwick Manufacturing Group, a high-profile part of the University of Warwick that is based in Coventry. It was Bhattacharyya who invited the Geely chairman Li to the city in the mid- to late-2000s, after previously meeting him in Beijing.

Lord Bhattacharyya - chairman of Warwick Manufacturing Group - introduced Geely’s chairman Li Shufu to Coventry and paved the way for the new investment

Lord Bhattacharyya - chairman of Warwick Manufacturing Group - introduced Geely’s chairman Li Shufu to Coventry and paved the way for the new investment

Bhattacharyya says: “I’m interested in cars and so is Li Shufu – so it seemed natural he’d like to visit Coventry [a historic centre for UK vehicle production]. He wasn’t all that interested in taxis – taxis were taxis, and no one bothered with them – but then Manganese Bronze came to his attention and he got involved with the company.”

Bhattacharyya says Geely’s plans for Coventry are “very encouraging”. He describes Li – who has humble roots and started out in business by buying an old camera to photograph tourists at beauty spots - as a “man with ideas and a vision of the future”.

“I’ve always said that the UK car industry can do well under the right sort of leadership and what Geely is doing in Coventry bears this out,” Bhattacharyya adds.

by Peter Marsh

Dyson's tilt to Asia fuels UK criticism

The decision by Sir James Dyson to choose Singapore as the manufacturing base for his foray into electric cars is a chance missed for Britain. It will disappoint many who had hoped the entrepreneur would follow up his large UK investments in engineering with a production venture.

Sir James – founder of the electronics and appliance business that bears his name – is with little doubt Britain’s best-known living engineer. He and his £3.5bn-turnover company demonstrate the country’s capabilities in technology and innovation.

The inventor has been a huge supporter of UK talent. His business – wholly owned by the Dyson family – employs 4,600 people in Britain, half of them scientists and engineers. Many are young technical specialists hired from universities and colleges.

The unspoken message behind Dyson’s announcement is that Sir James feels far more comfortable manufacturing in Asia than in the UK. He would argue that this stance, no matter how much it might annoy some people, is entirely logical on account of the continent’s rapid rise as an industrial powerhouse in the past 40 years.

Sir James shut down his company’s UK production in 2003, citing difficulties in sourcing key components for vacuum cleaners and other electronic appliances. Like others at the time, he also pointed to what he reckoned was a serious and possibly irreversible weakening in Britain’s manufacturing culture.

More recently – and more controversially - Sir James has become a fervent supporter of the UK decision to quit the European Union. He thinks Brexit will allow the country to shake off burdensome bureaucracy and forge new ties in fast growing markets away from Europe.

The electronics pioneer has many strong personal qualities. He is famed for his persistence in developing new “bagless” cleaners, where he fought against doubters including many representatives of big companies who said his ideas would never work.

Having seen off most of the naysayers and chalked up impressive success in other products including novel electric motors, air dryers and domestic fans, Sir James’s £2bn venture into electric transportation is based on his company’s existing expertise in motor technology together with new work in solid-state batteries.

Prolific inventor Sir James Dyson has launched new products including novel home fans but has decided against Britain as a place to make electric cars

Prolific inventor Sir James Dyson has launched new products including novel home fans but has decided against Britain as a place to make electric cars

The years of battling against the odds have given Sir James an outsider’s mentality. His technical brilliance is matched by a go-it-alone approach marked by extreme reluctance to collaborate with others, for instance in shared business ventures or education projects.

The entrepreneur’s obsession with secrecy is well known, as his interest in pursuing legal action against rivals he believes are infringing Dyson’s intellectual property. Sir James’ easy manner masks a deep sensitivity to criticism.

These aspects to his character may partly explain why Sir James was more disposed to setting up his new manufacturing facility in Asia than in UK – where scrutiny of his plans by politicians, industry rivals and media would have been far more intense. In Asia Sir James comes across as an exotic and wholly admirable business figure.

The decision to site the plant in Singapore fits in with Dyson’s long-standing ties in the city state, where the company sites much of its existing production. The company has other plants in Malaysia and a big following in Japan. It sees China as a big and expanding market for the new venture.

The Singapore move is by no means an unalloyed blow for Britain – where much of the engineering work for the project will continue to be done. Yet the decision to turn elsewhere for the new factory still looks questionable on several grounds.

Much of the automotive-related supply chains that Dyson will need for the new enterprise are more likely to be found in Britain and the rest of Europe than in and around Singapore. While siting engineering development and production thousands of miles apart may make sense in small electrical products, it looks a more dubious strategy in a product field such as cars that are bigger and much more complex.

Looming over the decision-making is Brexit. Some onlookers – though not presumably including Sir James – believe the traumas of the EU departure could derail whatever car industry and broader manufacturing renewal might be taking place.

One conclusion from the electric car imbroglio is that Sir James has turned down a golden opportunity both to demonstrate faith in a robust post-Brexit role for UK industry and to show confidence that Britain can prosper in the new field of electric car production. We must hope that while Sir James has ducked the challenge, others will make stronger bets on Britain’s manufacturing future.