An electric car start-up from Sweden has shrugged off worries about Brexit by choosing Britain for its main global factory, citing the country’s strengths in specialist engineering and availability of high-quality recruits.

Swedish car innovator switches to UK despite Brexit concerns

Lewis Horne, the 34-year-old chief executive of Uniti, says he has been influenced by the UK’s leading position in the engineering needed for high-performance cars, especially lightweight materials. “The Brits invented production of composites [blends of materials useful in cutting vehicle weight],” says Horne, who started Uniti in 2016.

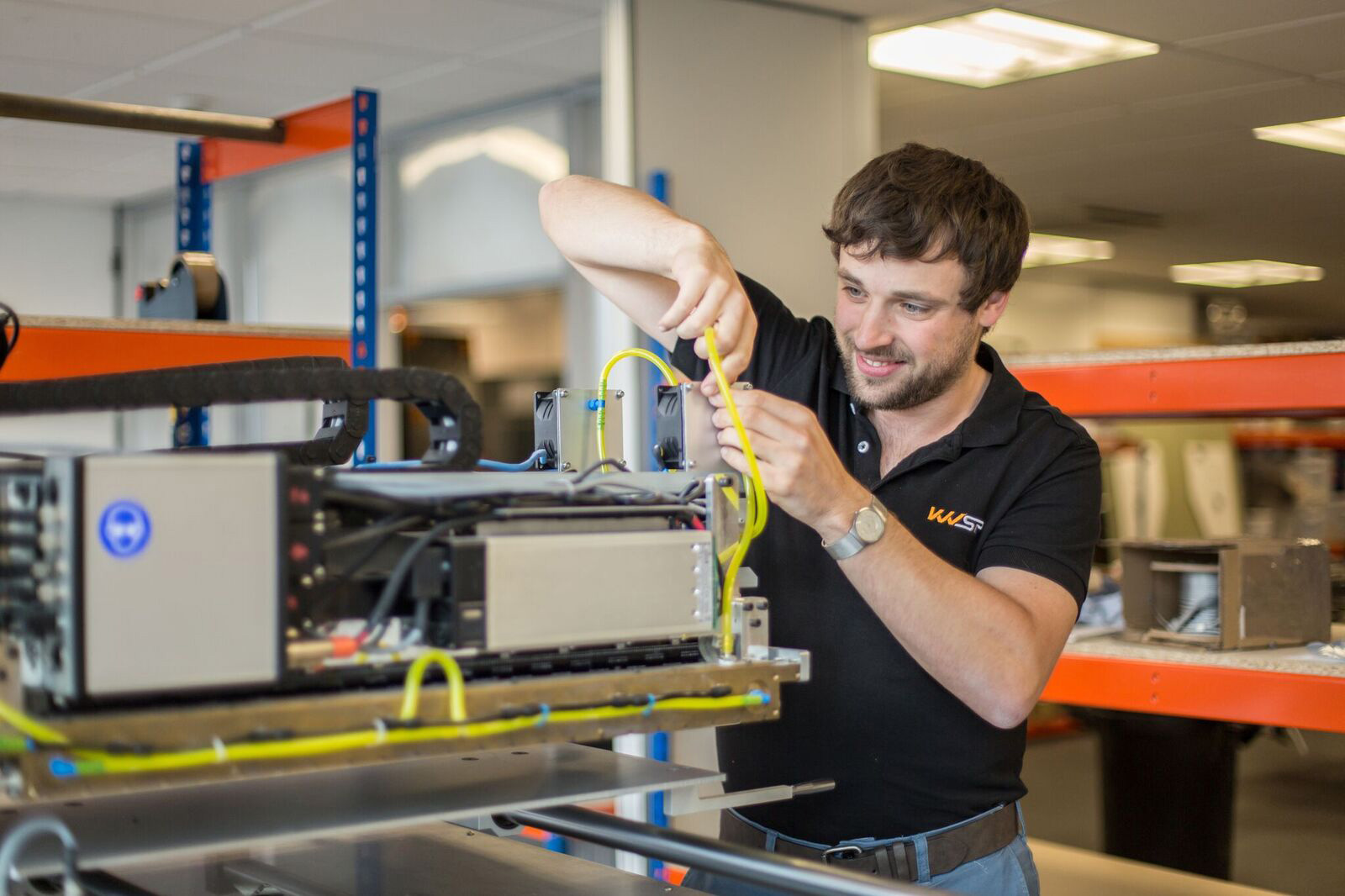

Uniti plans to build “resource efficient” battery-powered cars based on plastic composite materials and 3D printing rather than conventional processes such as cutting and welding. 3D printing is an evolving technology useful for making intricate shapes in small volumes, with a big potential for saving weight by cutting out unnecessary material. Some of Uniti’s development team are pictured above, with a prototype car.

The new factory is being built at Silverstone, Northamptonshire, close to the famous racetrack, home of the British Grand Prix. The plant is set to support other Uniti “satellite” factories around the world and to employ 200 people by 2021.

The Swedish company aims to become a pioneer in “digital manufacturing” where a range of suppliers can be integrated by connecting their supply chains and design systems electronically to create an efficient form of production.

“We wanted to find somewhere that would enable us to scale-up our ideas [for lightweight electric cars] to create mass-produced vehicles,” Horne says. “Silverstone was the best place where we thought this could happen.”

Silverstone’s history as a centre for vehicle engineering played a part in the decision. “I’m a branding guy,” he says. “People associate Silverstone with motor racing and high-performance engineering. This is important for our plans.”

The venture highlights the opportunities in the UK, of the sort Made Here Now wants to highlight, for young people taking up manufacturing as a career. It is also a reminder that, despite the uncertainties over Britain’s planned European Union departure, a significant corps of manufacturers is pushing ahead with new ventures.

The accompanying stories show how four manufacturers are planning to expand by adopting a range of strategies to counter any negative Brexit effects.

Horne has enlisted several engineering and supply chain businesses in the UK to help him in his plans. They include KW Special Products, a maker of composite materials based on 3D printing technologies.

Kieron Salter, KWSP’s managing director, says his business is planning to spend “several million pounds” on a plant in Silverstone that will make 3D-printed components forming part of Uniti’s new vehicles. He describes Horne as “a very fluent disrupter, driven by the idea of digital manufacturing”.

KWSP is a leader in precision manufacturing and is among Uniti’s technology partners

KWSP is a leader in precision manufacturing and is among Uniti’s technology partners

Salter says Uniti’s plans for the UK underline “what Britain is good at” in manufacturing. “Where Britain stands out is not necessarily on [manufacturing] costs but on research and development and innovation. The UK’s advantages lie not with competing with China but with rapid response and agility [in supply chains].”

Other businesses with which Uniti is collaborating include Unipart, a logistics company that specialises in organising supply chains; Danecca, producer and developer of electric batteries; German electrical goods giant Siemens, which is an advanced proponent of digital manufacturing and has a strong UK presence; and Williams, the Formula 1 racing car producer.

Richard Hankinson, automotive director at Unipart, says Horne is a “visionary, dynamic leader”. He thinks Uniti is best described not as an automotive business but as a “technology company producing a mobility product”.

Cars from the factory would sell for roughly £22,000 upwards. They could be made available to customers through a range of pathways including leasing by the day or hour.

“We are rethinking the possibilities for vehicles,” says Horne. “We want to create resource-efficient mobility that’s accessible to anyone. “I’ve found in many countries an incredible motivation [by engineers] to want to play a part in making this sort of product. This should help us to attract the employees we want, from Britain as well as from other places around the world.”

Uniti’s plans are ambitious and it faces several difficulties. It has joined the many other businesses (including some of the biggest automotive groups) working on electric vehicles to help cut carbon dioxide emissions and global warming.

Among the leaders is the US’s Tesla, started in 2003 by the entrepreneur Elon Musk. In 2018, Tesla delivered almost 250,000 cars and aims to make four times this many by 2020.

Uniti’s vehicles will be made using 3D printing and are meant to appeal to people keen on ecological living

Uniti’s vehicles will be made using 3D printing and are meant to appeal to people keen on ecological living

But Tesla has found it hard to maintain sales growth and increase output from its highly automated plant in California, resulting in Musk’s announcement in early 2019 of cuts of 3,000 jobs, or 7 per cent of the company’s workforce.

Uniti must raise almost all the £350m it thinks it will need for investments over the next few years. It wants to make between 20,000 and 50,000 cars a year from its UK factory from around 2021. Output should increase over several years to annual volumes of about 300,000.

Nissan’s car plant in Sunderland – the UK’s biggest automotive factory - makes roughly 500,000 vehicles annually but has built up steadily over more than 30 years.

Also, not everyone feels the UK is the best place for a new electric car plant. In 2018 Sir James Dyson, owner of the Dyson technology and appliance company, chose Singapore rather than Britain as the site of its first electric car factory.

Dyson has since announced his company will move its headquarters to Singapore from Britain.

On Brexit, several large companies including Airbus and Jaguar Land Rover have warned about how the lack of clarity– for instance about how new customs rules could affect European-wide supply chains - is likely to hit spending on new UK projects. The EEF manufacturers’ trade body says “the spectre of Brexit” has hit investment plans generally.

Horne however says he isn’t worried: “I wouldn’t say our plan is Brexit-proof – it’s Brexit-resilient”. If an EU exit makes exporting difficult or subject to high tariffs, Horne says the UK plant would make vehicles mainly for the British market, with minimal exports, and with Uniti’s satellite facilities elsewhere handling sales to mainland Europe.

Lewis Horne, Uniti’s 34-year-old chief executive, was drawn to the UK by its speciality engineering suppliers

Lewis Horne, Uniti’s 34-year-old chief executive, was drawn to the UK by its speciality engineering suppliers

Whatever shape Brexit takes, Horne feels Uniti will be able to organise knowledge transfer - engineering ideas and expertise – from Britain to the rest of its factory network with few restrictions.

Countries where Uniti could have production facilities apart from the UK and other European nations include the US, China, India, Japan and United Arab Emirates.

Brexit strategies

Reshoring

New UK plant preserves advantages for food packaging maker

Britain’s European Union exit could make it harder for UK-based businesses to import products from the rest of Europe, should onerous customs restrictions kick in.

To ease such difficulties, some companies have said they will add to their UK manufacturing operations through “reshoring” - and this is the path adopted by Aegg, a maker of plastic packaging for the food industry which is starting production in 2019 at a new plant in in Eye, Suffolk.

This is the first time Aegg has had its own factory in the UK. It has had its products made in Britain before, but by contractors.

Aegg managing director, Jamie Gorman, pictured left, with the company’s owner Anthony Coats (centre) and sales director Richard Drayson.

Aegg managing director, Jamie Gorman, pictured left, with the company’s owner Anthony Coats (centre) and sales director Richard Drayson.

The £2.1m investment will lead to a “significant” rise in the amount of Aegg’s products made in the UK, the company says. At present, Aegg’s packaging items are produced in several factories worldwide, mostly run by other manufacturers.

Jamie Gorman, managing director, says the new unit “will allow Aegg to better serve customers who would otherwise be adversely affected [by supply chain disruptions] …. in the aftermath of Brexit”.

It will also help meet expanding UK demand for the company’s plastic food pots and bowls, and give the company more opportunity to invest in new products. Gorman believes Aegg will have more leeway to introduce novel ideas into its manufacturing – such as through new designs or plastics tooling - if it has its complete control.

Aegg has just a handful of employees at the Eye plant but says this should rise to about 55 during 2019/20 as production ramps up.

Trans-Atlantic trade

Digger supplier strikes US pay dirt

Connor McGuckin, design engineer at Strickland Ireland, a maker of specialist equipment for the excavator industry, says strong interest in his company’s products from the US is behind its decision to add significantly to its UK operations, mainly through a £250,000 investment in technology and engineering.

The investment has resulted in Strickland adding to its engineering and design team at its base in Coalisland, Northern Ireland, which employs about 26 people.

The move will shift Strickland over the next few years to become less of an orthodox manufacturer and more a design and development business that leaves most of its production to contractors.

While McGuckin describes Brexit as “a mess”, he thinks his company can bypass any negative repercussions by focusing on the US market. “I don’t see restrictions [on US trade] being applied heavily if at all, “ says McGuckin. “I feel …[Donald] Trump will provide a good trading deal [with the UK].”

Brexit is a "mess" says Connor McGuckin of Strickland but he thinks his company can avoid negative effects

Brexit is a "mess" says Connor McGuckin of Strickland but he thinks his company can avoid negative effects

Fortunately for Strickland, the US is where it sees the biggest opportunities for its products –which include intricate coupling devices that anchor attachments such as buckets to excavator arms.

In 2018, just over half its sales of about £4m were exported to the US, 40 per cent sold in Britain, with mainland Europe accounting for 5 per cent. In the next few years, McGuckin thinks US sales will climb to 70 per cent of a growing revenue number. Sales in 2019 are expected to be £5m.

To cater for increasing demand, the company is stepping up its use of contractors for manufacturing, rather than relying on inhouse staff.

Local supply chains

Gearbox specialist sees smooth road ahead

Xtrac occupies a niche in the automotive industry - it makes gear boxes for Formula 1 racing vehicles and other high-performance cars. The Berkshire-based company also exports 80 per cent of its sales, with most of this going to mainland Europe.

Prime minister Theresa May found time during Brexit discussions to visit Xtrac’s expanding factory in Berkshire

Prime minister Theresa May found time during Brexit discussions to visit Xtrac’s expanding factory in Berkshire

This might cause Xtrac worries about the UK’s planned European Union departure, with its potential to seriously disrupt trade between Britain and the rest of Europe. Not so, says Stephen Lane, Xtrac’s finance director. “We don’t see any significant risk of a downturn [related to Brexit],” Lane says.

Behind this confidence is partly Xtrac’s highly concentrated supply chain – comprising predominantly UK-based businesses. Most of them are located in the arc between Surrey and Northamptonshire, which is home to many engineering suppliers in Formula 1 industry. “We have very little [supply] from continental Europe, which in the Brexit context is positive,” says Lane.

Another insulating factor, he reckons, is the specialist nature of what Xtrac does, which restricts the amount of competition. Its customers in continental Europe are likely to stay loyal to the UK company, Lane says, even if Brexit does result in trade frictions and possible higher prices.

The specialised automotive maker is gearing up for growth by recruiting more apprentices including Chloe Noble who joined in 2018

The specialised automotive maker is gearing up for growth by recruiting more apprentices including Chloe Noble who joined in 2018

On the back of such sentiments, Xtrac is investing £22m over four years in expanding and upgrading its manufacturing base in Thatcham near Newbury. It has an “aggressive” programme of recruitment with a strong focus on taking in apprentices and graduate engineers.

The company’s sales in the 2016/17 financial year came to £50m and it employs 350 people, 70 more than at the end of 2016.

Product strengths

Suitcase maker Trunki travels hopefully

In 2012, Trunki – a UK company making brightly coloured children’s suitcases – switched production to the UK from China. The investment in opening a production centre in Plymouth has proved a winner, says Rob Law, Trunki’s founder and chief executive. But could Brexit cause Trunki to rethink its plans?

That’s unlikely says Law. He sees such strong possibilities for expansion, even with much of the company’s production exported to continental Europe, that there is no need to abandon Trunki’s UK-centred manufacturing focus in favour, for instance, of shifting at least some production to mainland Europe.

The approach adds up to “business as usual”. Law feels Trunki’s strengths in product design and marketing are enough to overcome any difficulties that lie ahead.

“Obviously we are looking ahead with some caution,” says Law. “But if Brexit does lead to higher costs [in relation to moving goods from the UK to the rest of the EU] we feel we can cope.”

Trunki’s suitcases can be treated as hand luggage on aircraft. They are meant to provide amusement and fun as well as being useful for carrying such things as favourite toys. They come in a wide range of styles and have won awards for innovative design and manufacturing.

Trunki's plastic suitcases for children have become a feature at many airports

Trunki's plastic suitcases for children have become a feature at many airports

Law reckons Trunki’s annual sales – now running at about £9.5m – will grow by “a few million” over the next few years with “huge possibilities” for pushing up revenues from France and Germany. “We will need 50 per cent more capacity [in production] to keep up with demand,” he says.

To help cope with any impediments to exporting, Law is exploring partnerships with distribution businesses in continental Europe. These could provide warehousing and logistics services to ease supply disruptions.

Trunki plans to invest £500,000 in new tooling and machines at the Plymouth facility – which employs 55 people – to support the expansion.