Dozens of separate processes are needed to create Plessey’s new type of semiconductor, which could bring big benefits for the global lighting industry

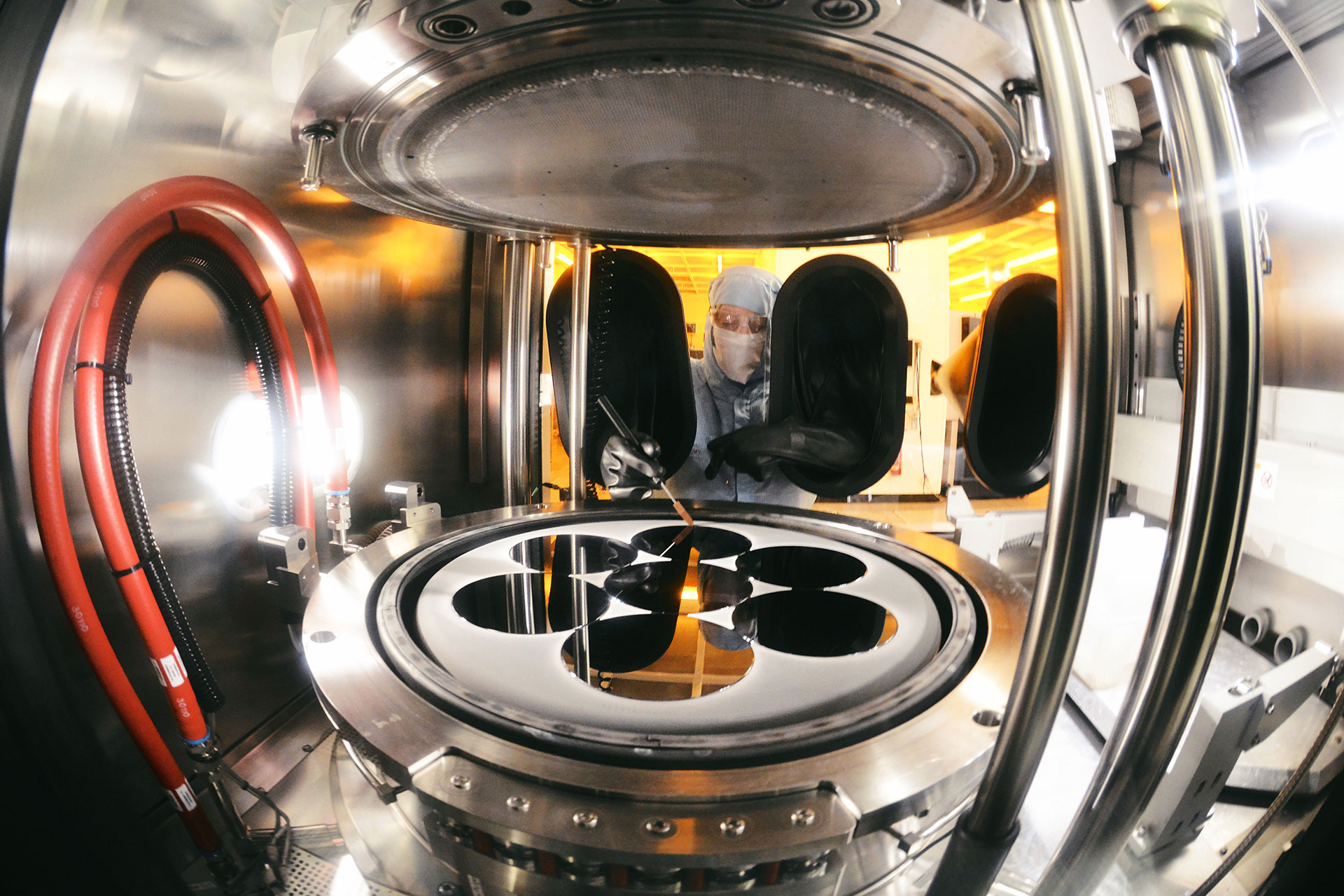

Photo by Dan LynchPlessey’s manufacturing process requires high-tech clean rooms capable of excluding even the tiniest dust particles

Photo by Dan LynchThe company has invested £60m in advanced equipment that can apply wafer-thin layers of chemicals to a silicon base

Photo by Dan LynchFew of the products are ever touched by human hands

Photo by Dan LynchPlessey’s processes are based around making light emitting diodes – the semiconductor-based light sources that have revolutionised the global lighting industry

Photo by Dan LynchThe Plymouth company is setting out to be a “technology disrupter” in an industry populated by much bigger players

Photo by Dan LynchNew ideas in production and design have come through developing processes developed at Cambridge University

Photo by Dan LynchMichael LeGoff, chief executive, says he wants to spearhead “the revitalisation of the electronics manufacturing industry in Britain”

Photo by Dan LynchDriving the technology is a way to configure lighting chips to suit specific applications before they leave the factory, making it easier to meet customer needs

Photo by Dan LynchPlessey’s processes are based around silicon rather than more exotic materials, giving engineers a broader range of existing technologies they can use in manufacturing

Photo by Dan LynchThe company faces an uphill struggle to get ahead in the face of tough competition

Photo by Dan LynchBritain has a proud record of innovations in electronics – but has done a poor job of turning these into sustainable businesses that create large numbers of jobs.

After World War Two, UK engineers built some of the world’s first electronic computers, among them Cambridge University’s EDSAC machine (electronic delay storage automatic calculator) which was completed in 1949.

In the 1970s, the UK was responsible for three of the world’s leading electronics companies: Plessey, GEC and the computer manufacturer ICL. In the 1980s, Ferranti, another pioneering UK firm, was responsible for a number of innovations including so-called gate-array chips – a form of “customised” or “application-specific” semiconductor.

Now that these one-time electronics leaders have all disappeared, UK electronics manufacturing is represented mainly by a few sophisticated companies turning out mainly small quantities of high-value products on behalf of bigger businesses on an “outsourcing” basis.

Such “contract manufacturers” include Briton and Paragon, both based in Bedford, and US-owned Plexus, which operates a plant in Bathgate, Scotland. Such companies make products such as medical devices or control equipment, normally sold under other companies’ brands.

Besides Plessey, Britain is home to a handful of other semiconductor manufacturers. One of the few UK-owned businesses is Semefab, based in Glenrothes, Scotland. Infineon of Germany operates a plant at Newport in South Wales, while NXP of the Netherlands makes chips in Stockport, near Manchester.

The area in and around Cambridge has a notable “cluster” of small electronics businesses, many with links to Cambridge University. Bristol and nearby towns are home to about 30 electronics firms – many of which were set up or staffed by skilled engineers and technicians who at one time worked for Inmos, a state-owned semiconductor business started in the city in 1978.

Inmos was responsible for a number of technology successes – including the “transputer” microprocessor. But it failed to meet its commercial targets and was privatised in 1984, disappearing from view a few years later.