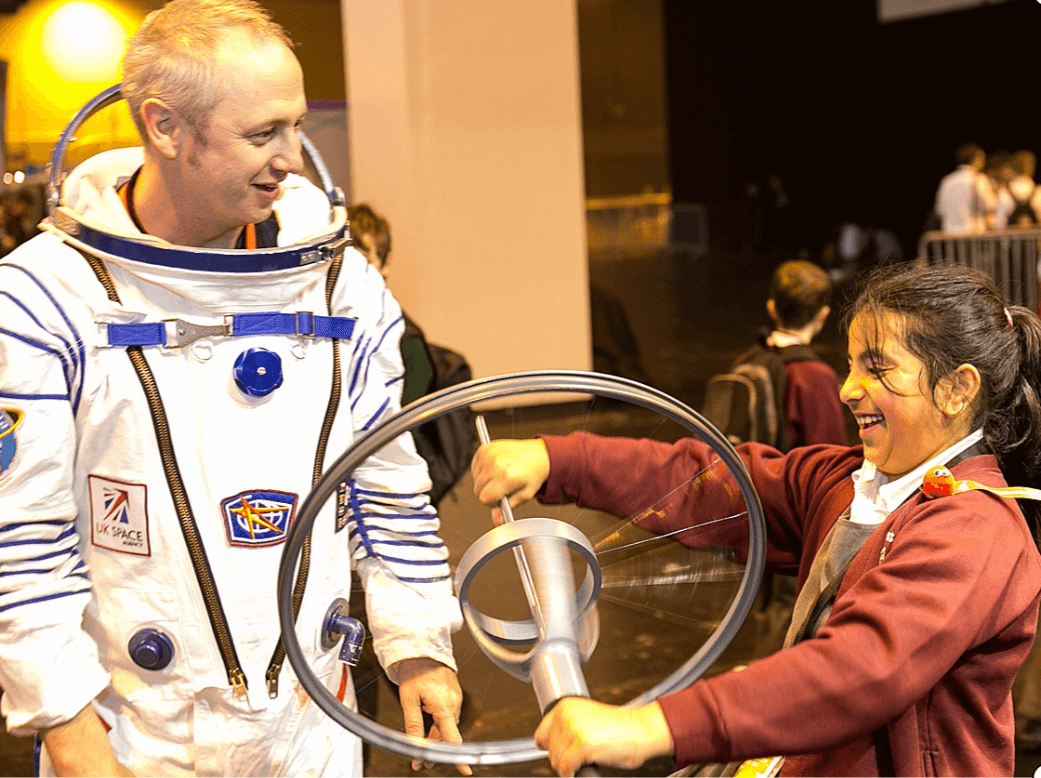

An early interest in science and technology - sometimes nurtured by a teacher or family member - is often a key factor leading to an industrial career

UK ‘not doing enough’ to attract young people into industry, say academic leaders

Efforts to attract more young people into manufacturing and engineering continue to fall short of what is needed to arrest skills shortages, say academic specialists, following a Made Here Now study of how people move into these careers.

Full results from the research – examining the career paths of 107 young men and women working for 76 UK manufacturers – are available here. The survey gives insights into key influences including family relationships, advice from teachers and employer outreach, including school events, work-based learning and factory open days.

According to a 2020 Department for Education report, 36 per cent of job vacancies in manufacturing were related to skills shortages, the highest figure for any part of the economy apart from construction. The equivalent figure two years earlier in a previous DfE survey was 29 per cent.

The lobbying group EngineeringUK – which looks at engineering across many sectors including manufacturing – has published research indicating that skills shortages are likely to lead to at least 100,000 unfilled vacancies per year in engineering-related positions up to 2024.

Rhys Morgan, head of education at the Royal Academy of Engineering, said: "It is fair to say collectively that we have not moved the dial any great distance [in attempts to make engineering more attractive to young people] despite all the efforts over the past 20 years. Much of this has been because providers [in education and industry] have never really tested how effective or impactful their programmes to encourage young people into engineering have been."

Philip Greenish, chair of the governing council at Southampton University and a former chief executive at the academy, said that while he now never hears “ignorant comments about engineering as I used to from some supposedly educated people", he worries that the underlying “structural issues" holding back numbers going into manufacturing and engineering remain “pretty much as bad as ever".

Discussing the influences highlighted in the survey that were likely to inspire young people to choose engineering and manufacturing, Johnny Rich, chief executive of the Engineering Professors' Council, said planned interventions to boost numbers should be "long-term and sustained" rather than "fleeting and momentary". Rich added: "Short-term interventions are pointless. This is like giving people a springboard without a swimming pool."

James Kinsella, director of Bluetree, a print supplier and face mask manufacturer in Yorkshire, said the study was a reminder to employers about the need to "build an exposure" with young people, while Lizzie Crowley, senior skills policy adviser at the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development, said: “The research backs up existing literature on the influence of educators, parents and employers on career decisions and choices made by young people."

Of the 107 people in the Made Here Now survey, 28 per cent say teachers and careers advisers at school played a crucial role in promoting the idea of working in manufacturing with 26 per cent citing the role of a company, for example via a factory “open day". Allowing for those who named both sets of interactions, the total identifying at least one comes to 48 per cent.

In addition, 45 per cent of the sample say a family member – such as a parent working in engineering or production – influenced their decision to seek a job in manufacturing.

The Made Here Now research involved interviews with people aged between 20 and 32 working in sectors from aerospace to mattress manufacturing. Of the sample, 65 did an undergraduate degree, with 39 studying engineering, 11 taking a science subject and another 11 degrees involving design, sometimes combined with engineering. Of the cohort, 22 have a postgraduate degree and 38 were apprentices.

Part of a family that came to the UK as asylum seekers, Shrouk El-Attar gained five A-levels and a master's degree before starting work in the electronics sector

Part of a family that came to the UK as asylum seekers, Shrouk El-Attar gained five A-levels and a master's degree before starting work in the electronics sector

The study features several people who faced tough challenges as they moved into manufacturing. While Shrouk El-Attar was "fascinated" by engineering and electronics during her schooldays in Egypt, her life took a negative turn when her family was forced to flee to the UK to seek asylum.

Left to fend for herself after other family members were deported, El-Attar gained five A-levels, followed by a master’s degree at Cardiff University in electrical and electronic engineering. After a design job at the Renishaw engineering group, El-Attar works at Elvie, a Bristol company specialising in products for women such as breast pumps.

Rhuvi Wickramasingha says in his late teens he had “really had no idea of what I wanted to do with my life". After learning about computerised textiles machines in a job with his aunt's knitwear business, he says of his job as a knitting technician at Jack Masters, a Leicester clothing manufacturer: "I am in an occupation which I like, and which offers a way to use a combination of design and cognitive skills."

Supportive teachers have often played a part. At school Alex Stokoe says he was interested in technical subjects but found engineering daunting. Don Sayers, who taught electronics at Verulam secondary school in St Albans, Hertfordshire, was “passionate about explaining how things work" and “helped me to grasp more clearly what engineering was about". Spurred by these ideas, Stokoe went on to an engineering degree and found a job at the TTP technology consultancy where he works on manufacturing and product development.

Jessica Scully admits that at school she “misbehaved and didn’t give lessons proper attention - I feel I squandered my time". She says two teachers at Washington Academy in Northeast England encouraged a shift in approach.

Scully says of Derek Austwick, now the school's deputy-head, and Len Debbage, a technology teacher: “Mr Austwick didn’t take any of my nonsense. He told me I could achieve a lot if only I put my mind to it. And Mr Debbage would give me a cup of tea and say: ‘You might think the world’s against you but it’s not’."

Jessica Scully says she is grateful to two school teachers who said she could achieve a lot "if she put her mind to it"

Jessica Scully says she is grateful to two school teachers who said she could achieve a lot "if she put her mind to it"

After collecting just three GCSEs, Scully says she was shocked into change. She studied aerospace engineering at college, followed by a degree in mechanical and manufacturing engineering at Teesside University. In 2017 she joined Roman Showers in Newton Aycliffe where she oversees the quality department. “It's a lovely company with a supportive environment," she says.

Someone else whose schooldays featured difficult moments – right at the very end – was Tom Queen, who as a boy had a great interest in computing. “As an experiment I hacked into the school’s servers. I left a note on the system saying the school should review its security procedures. Unfortunately, the school management didn’t appreciate this and kicked me out."

But his brush with adversity did not set him back for long. Prior to his expulsion, Queen says he had been lucky to do a two-week spell of work experience in the robotics department at the University of Plymouth.

“I absolutely loved doing this. It opened my eyes to the opportunities in robotics." Later this took him to Shadow Robot, a maker of robotic hands, where he says his job as a software engineer has “turned out brilliantly".

As a general way to encourage more people to follow routes such as Queen’s, Johnny Rich of the Engineering Professors' Council says schools should lower some of the barriers to learning about science at school.

He says the number of young people moving into jobs related to engineering and other technical areas would rise if more pupils were able to study “triple science" at GCSE – where they learn about biology, chemistry and physics as separate subjects – rather than being limited to just one or two of them unless they have previously performed well academically. “Every pupil, regardless of ability, should be given the chance to study science at a high level at school," Rich said.

Concerns over curriculum and apprenticeships cloud skills outlook

Declining apprenticeship starts during the pandemic and a collapse in the numbers taking GCSE Design and Technology are stoking fears of a long-term shortage of recruits with the skills manufacturing companies require.

Rachel Gamble, human resources manager at John Smedley, a Derbyshire-based knitwear maker, says: "From our experience it isn’t getting easier to attract apprentices or younger people into textile manufacturing positions. While we have had some successes, we find when we advertise such jobs, we get few applications. Manufacturing work is not something that is actively promoted in schools/colleges. [It’s seen] by students as old-fashioned."

Others say the health crisis has added to the pressures. Apprenticeship starts in engineering and manufacturing have fallen steeply, in part due to difficulties of organising courses during a pandemic. This is likely to slow the flow of potential recruits to industry in coming years.

Andrew Churchill, chairman of JJ Churchill, an aerospace manufacturer based near Leicester, fears for the future of many engineering-related courses at further education colleges which financial pressures may forcibly close, so putting future apprenticeship schemes even more at risk.

Taylor Gore followed his father into a job making luxury beds and mattresses for Savoir - "I was happy to follow his example" he says

Taylor Gore followed his father into a job making luxury beds and mattresses for Savoir - "I was happy to follow his example" he says

Alistair Hughes, managing director of Savoir, which makes luxury beds and mattresses, said UK companies making specialised products to high standards had a big advantage in that "consumers around the world love British-made products [of this genre]". But Hughes is frustrated by what he sees as failings in the education system.

“We [in UK industry] are limited by the absence of a world-class apprenticeship system and lacklustre appreciation of manufacturing and technical education. We welcome anything that schools and employers can do to change perceptions."

A big decline in design and technology teaching in secondary schools, which could lead to fewer pupils developing an interest in subjects such as engineering, worries company executives. Government figures show that the number of design and technology GCSEs taken by 16-year-olds in England dropped by more than 70 per cent between 2008 and 2019.

Kenneth Cornforth, education director at the Baker Dearing Educational Trust, the organisation behind university technology colleges, makes a link between this decline and what young people may later choose to do as a career. "We are most concerned at the steep decline in design and technology teaching in mainstream schools. We want to encourage schools to give design and technology a greater importance in the curriculum and where necessary revitalise the way the subject is taught."

Johnny Rich, chief executive of the Engineering Professors' Council, argued that the course should be renamed “engineering and design". By making engineering concepts easier for pupils to understand and identify, the shift would help them engage with engineering subjects as they progressed, for instance through university courses.

The sky's the limit - the Made Here Now survey points to a range of experiences during a person's childhood and teenage years that may trigger an enthusiasm for engineering or design

The sky's the limit - the Made Here Now survey points to a range of experiences during a person's childhood and teenage years that may trigger an enthusiasm for engineering or design

For many pupils, engineering is a mix of topics that is hard to grapple with, Rich argues. “It's very hard to be what you cannot see," he said.

But some are more optimistic. David Osborne, chief executive of Roman Showers, which makes bathroom fittings in a plant in Newton Aycliffe, Durham, says he has found it “significantly easier" to recruit young people to manufacturing jobs over the past three to five years.

“Apprenticeship schemes are much better publicised and much better understood by schools as well as young people and their families." He added. “Many university courses are much better aligned to modern needs in manufacturing, so design, manufacturing and process-based graduates are more available – and better equipped to quickly adapt to life in business."

In areas of industry involving fast developing technologies such as 3D printing and robotics, the attractiveness of these disciplines to many young people has pushed recruitment down the list of concerns for senior executives.

Martin Thompson works as a medical visualisation engineer at 3D printing company Axial3D - whose chief executive says its "reputation for innovation" helps recruitment efforts

Martin Thompson works as a medical visualisation engineer at 3D printing company Axial3D - whose chief executive says its "reputation for innovation" helps recruitment efforts

Roger Johnston, chief executive of Belfast-based 3D printing business Axial3D, which makes models of parts of the human body to help in healthcare, says: “[Finding recruits] is getting easier because the specific skills we require – medical visualisation, 3D imaging and artificial intelligence – are being addressed by more university courses than three years ago. We benefit from a positive reputation for innovation and that helps us recruit. The flip side is that there is a lot of competition, especially in the AI engineering world, and that is driving salaries and competition up quickly."

Laura Gregory, a recruitment specialist at CMR, a medical robot maker in Cambridge, says in recent years it has become easier to find the people the company needs, partly due to its reputation as an “innovative and rapidly growing company with plenty of opportunity".

Also seeing a positive trend – at least for his company – is Rich Walker, managing director of Shadow Robot, a company based in London that makes robot hands used for applications including industrial assembly. Walker has a one-hour meeting with every new person starting work at his company. “What comes back to me again and again is that people want to join organisations that accept the huge challenges facing humanity and will act on them, and where they can be part of a team working together to do something special."

Helen Sanders, chief executive of Your People Partners, a recruitment adviser that works with companies including Shadow, said: “The role of employers in engaging with students at school or in further education can be hugely important. The image and values that the company presents will often be just as important as the salary [in attracting new employees]."