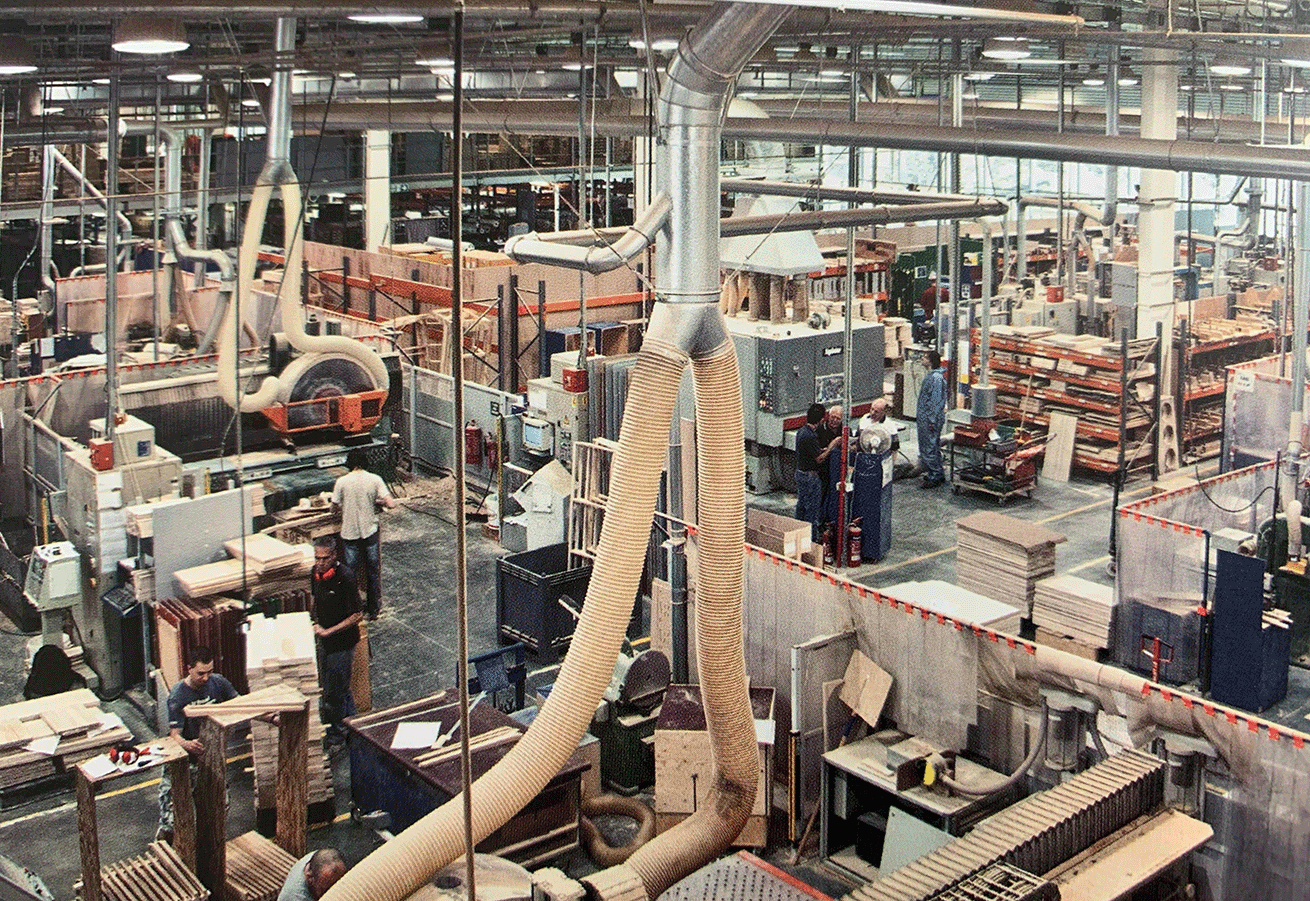

Ercol has added contemporary design ideas to an approach based on traditional English furniture production

Fashioning a future with flexible production

A century-old furniture maker known for its “cool classic”

designs is championing “hybridised” production – splitting manufacturing

between high- and low-wage locations to combine the benefits of both. For many

manufacturers, this represents a more sophisticated way to remain competitive

than simply “offshoring” production abroad or bringing factory operations back

onshore.

Ercol, which is family owned, has used hybridised production

to balance its UK and overseas operations which – along with investment in

design and training – has enabled it to prosper in difficult markets. Over the

past 30 years, other well-known furniture names have either disappeared or cut

back UK production drastically due to pressures including a big rise in

low-cost imports, lack of financial support and lacklustre management.

In continuing to operate a big domestic factory, Ercol is among a handful of wood-based furniture makers that have retained UK manufacturing

In continuing to operate a big domestic factory, Ercol is among a handful of wood-based furniture makers that have retained UK manufacturing

Ercol is based in Princes Risborough, Buckinghamshire, near

the historic furniture centre of High Wycombe, where it was started in 1920 by

Lucian Ercolani, an Italian craftsman and entrepreneur. "Our goal has been to find the right

blend between craft and tradition, and technology and innovation,” says Henry

Tadros, Ercol’s chairman and grandson of its founder. “We are proud we are still in business and

have found a strategy to grow.”

The hybridised system of production is not new but has

become an increasingly valuable approach for many manufacturers in western

Europe and the US where wages and other costs are high. Rather than outsource

all production to lower-cost regions, it often makes more sense to use a more

flexible approach that harnesses the design, technology and customisation

skills found in more advanced economies. The additional costs that result are

offset by relocating some production processes to lower-wage economies.

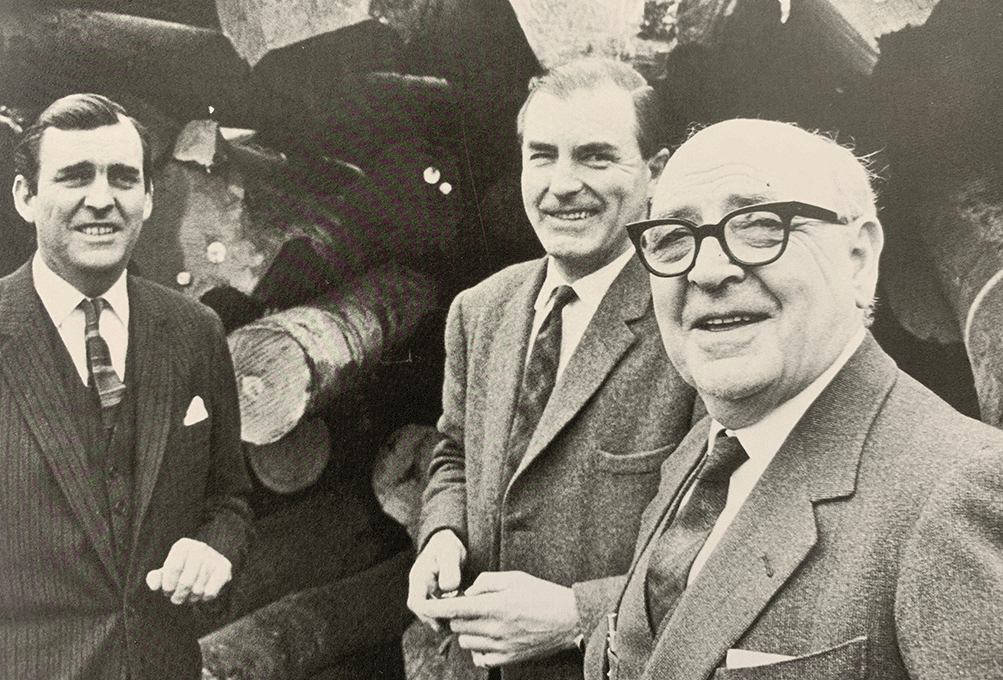

Italy-born Lucian Ercolani (pictured right) introduced a touch of continental flair when he started the company in 1920

Italy-born Lucian Ercolani (pictured right) introduced a touch of continental flair when he started the company in 1920

Ercol’s philosophy carries lessons for other firms - even

much bigger ones - seeking ways to grow. The 130-strong company had sales in

2022 of £20.3m, recording a small operating profit, against losses in previous

years. Ercolani’s descendants continue to own and run the company, with Henry

Tadros taking over as chairman in 2022 from his father Edward who held the top

job for 29 years.

Over its history, Ercol has built a reputation for its

furniture, using a mix of classic home-furnishing styles and more modern ideas.

It has retained a following for a signature “show wood” form in which the

underlying wood is exposed, sometimes behind cushions or other soft furnishing

material.

Lesley Graham, a director of Sterling Home, an independent retailer with a long connection to Ercol, has been “very impressed” with the

company’s resilience. “Like all manufacturing businesses, they have had to

adapt and look to other markets to perform certain tasks for them, but their

bigger view was always to maintain a manufacturing capability in the UK. Additionally I think they have been

clever in exploiting their heritage and have taken advantage of their reputation for

quality and hand build.”

Jordan Allsopp - facilities manager - says he appreciates the freedom to explore new ideas that he gets as part of the job

Jordan Allsopp - facilities manager - says he appreciates the freedom to explore new ideas that he gets as part of the job

A sign of Ercol’s interest in planning ahead is its efforts

to hire younger workers. With only about 20 per cent of Ercol’s employees aged

under 35 and many in their 50s and 60s, Ian Peers, operations director,

underlines that “it is evident we need to increase the number of young people

coming into the business”.

Jordan Allsopp,

Ercol’s facilities manager, who joined as an apprentice in 2015, illustrates

the company’s efforts. "I learn something new every day,” says the

26-year-old. “You have the freedom to

explore new things. I like the idea it’s a family business with a supportive

environment.”

The company works with top international designers in an effort to create elegance

The company works with top international designers in an effort to create elegance

Duncan McGrath-Simpson has responsibility for a big element of Ercol’s manufacturing

Duncan McGrath-Simpson has responsibility for a big element of Ercol’s manufacturing

Duncan

McGrath-Simpson, a 33-year-old manufacturing cell leader at the plant, is

similarly enthusiastic. "The job is a challenge,” he says. “Every day I do

something different."

In the mid-1970s, Ercol recruited about 20 apprentices a

year. As conditions grew tougher for the domestic furniture industry, the

apprenticeship scheme all but disappeared by about 2005, before the numbers

crept up again to one or two a year between 2017 and 2020. But in 2021, Ercol recruited seven

apprentices, followed by six in 2022. It aims to keep the number at around

these levels or higher over the next few years.

As well as its wood products such as tables, dining chairs

and cupboards, Ercol supplies upholstery-based items such as sofas and

armchairs. Upholstered items are generally bulky and expensive to ship. This

gives UK producers a cost advantage over importers and helps to protect

domestic manufacturing. Other established UK furniture brands such as

Parker Knoll and

G Plan continue to make upholstery products in the UK but have

withdrawn from the wood-based end of the business.

Design staff are not afraid to add colour

Design staff are not afraid to add colour

These points are noted by James Barker, managing director of

Barker and Stonehouse, a long-established

retailer that started selling Ercol products in 1948. “It is a great credit to Ercol that it is one of the only

remaining British manufacturers of cabinet [wood-based] furniture left in the

UK,” Barker says.

About half the company’s production is now done outside the

UK, with the rest in its home plant – where manufacturing processes are more

likely to involve a high degree of automation or craft skills that are more

difficult to replicate elsewhere. As well as reducing costs, the change to

hybrid production has brought added flexibility and made it possible for Ercol

to offer a broader set of products. In its offshoring, the company stresses its

careful approach. “We have been very selective of who we work with [in

offshoring],” says Henry Tadros. “Even

though we outsource a lot more of our production than we used to, we feel we

have maintained the Ercol DNA."

Over the next few years, the company could adapt its

manufacturing plans further. Global trends linked to Covid - and Brexit -related

supply disruptions plus the war in Ukraine are likely to lead Ercol to switch

more of its production to the UK. “Some of the weaknesses in the globalisation

model have given us an opportunity [for more UK production],” says Ian Peers,

operations director. Already, says David

Finch, Ercol’s managing director, the company is taking steps to “bring some

work back to the factory that was previously done in China”. Such moves are

likely to be introduced slowly but may in time give a modest boost to

employment at the UK factory.

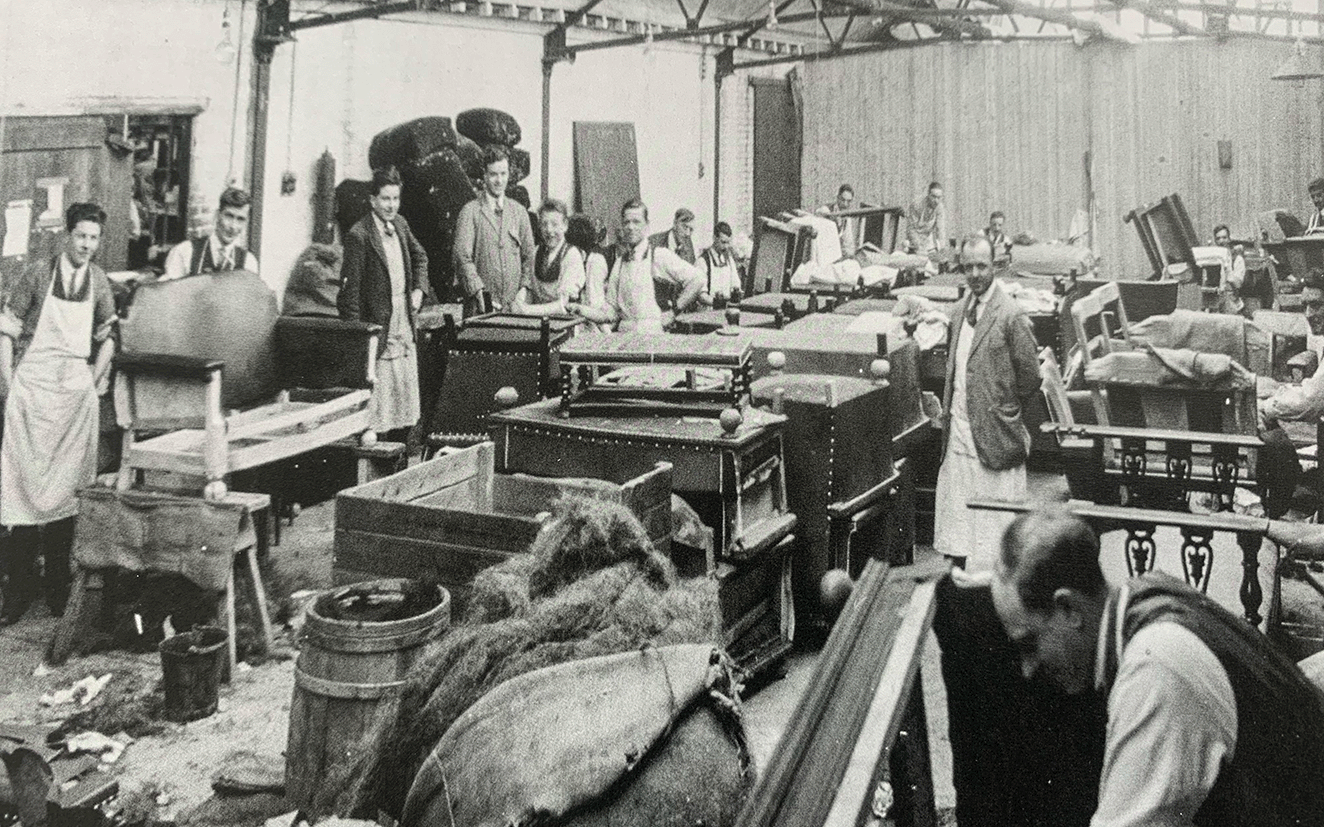

The company in its early history used production methods far more labour-intensive than today’s

The company in its early history used production methods far more labour-intensive than today’s

Other elements in the Ercol plan for growth have involved

refreshed designs. In 2018, it introduced in the

L.Ercolani furniture range

that added some design tweaks to its historic style. The range currently

generates sales of about £2m a year.

And in keeping with Ercol’s long tradition of working with

external designers, its five-strong in-house design team, led by creative

director Rachel Galbraith, collaborated on the L.Ercolani range with outsiders

including Norm Architects, a firm in Copenhagen, and

Tomoko Azumi, a

Japanese-born designer based in London.

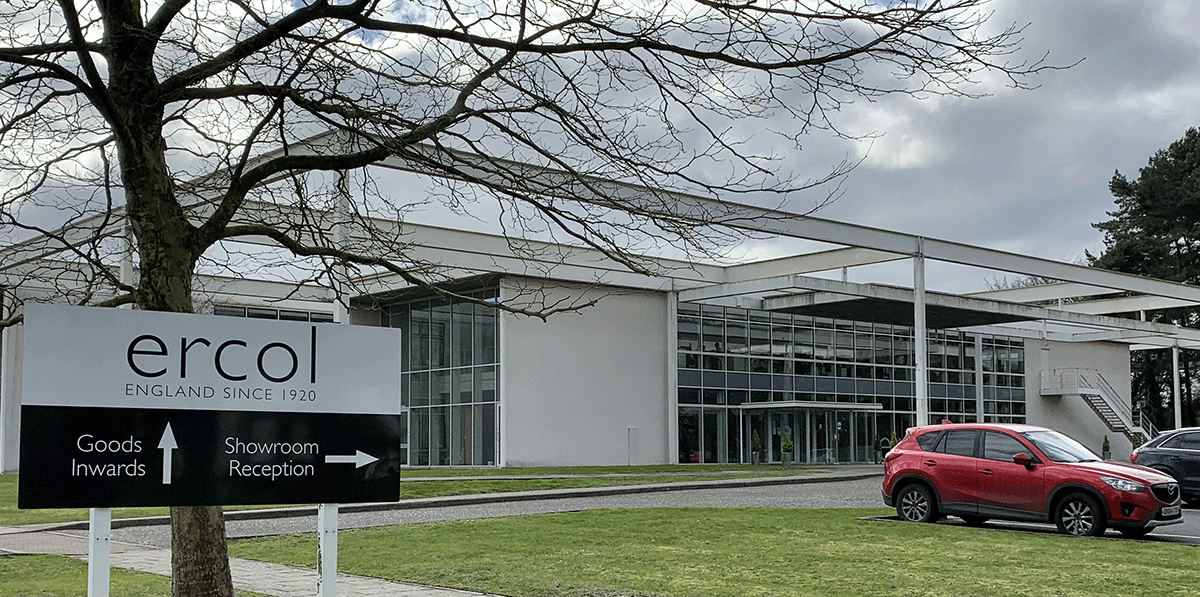

Furniture factory sets out vision for the future

Ercol’s “pavilion in the park” in Princes Risborough is a key part of its modernisation plan

Ercol’s “pavilion in the park” in Princes Risborough is a key part of its modernisation plan

A big part of Ercol’s plan has

been to invest heavily in its sleek and airy factory in Princes Risborough, which the company moved to in 2002 from

its historic base of High Wycombe. This town in the Chiltern Hills to the west of London emerged in the 1800s as a

centre for furniture manufacturing, mainly because of the large local supply of good-quality wood from beech trees.

The 2002 move carried risks, exposing the company for a short time to a big loan and requiring it

to revamp its manufacturing methods. At the time, Ercol took on debt that at one point reached £15m including

short-term borrowings to cover work in progress and land purchases – a heavy burden for a company that had revenues

of less than £20m in 2001.

But Edward Tadros – whose father started Ercol and whose son Henry is now chairman - emphasises

that the move was vital to demonstrate the family’s “faith in the future of the company and in UK manufacturing”. It

also opened the way for more efficient production methods than had been possible in the company’s previous cramped

and outdated facility. The new factory ended up costing £11m, with much of this recovered from selling the old site

for housing.

Inside the plant, the company has, since 2015, spent some £1.1m on automated machines for wood

cutting, allowing for speedier and more flexible production. Again this represented a substantial investment, judged

against the background of a furniture industry in relative decline.

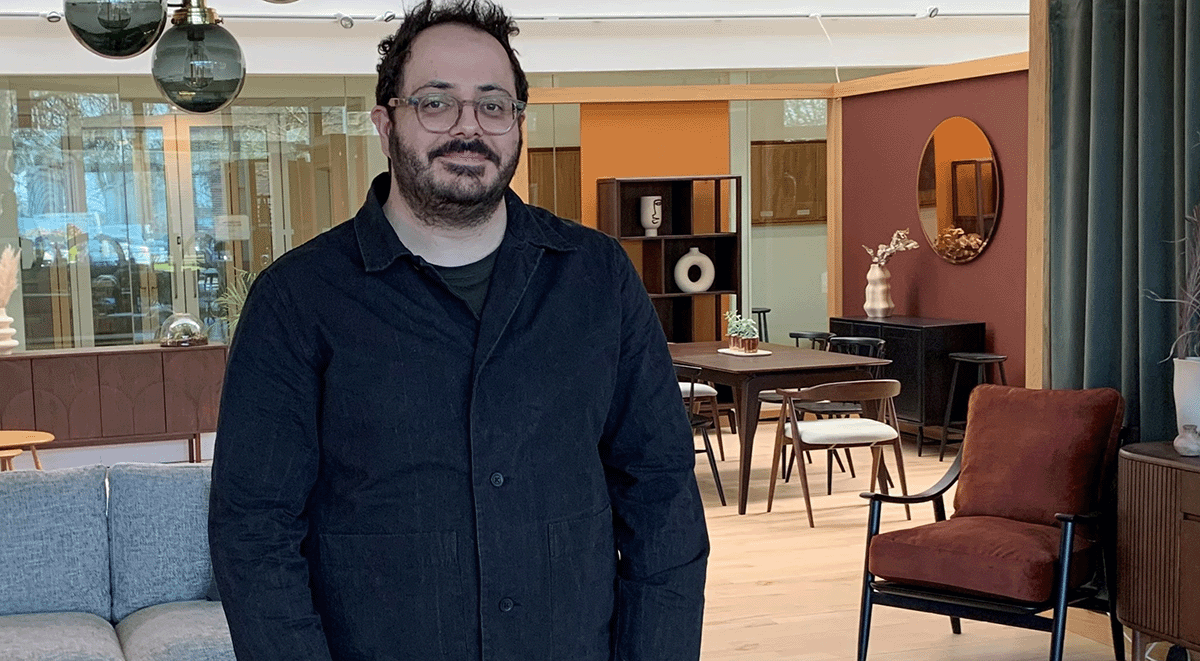

Henry Tadros, chairman, says the company seeks to blend “craft and tradition, and technology and innovation”

Henry Tadros, chairman, says the company seeks to blend “craft and tradition, and technology and innovation”

As for Ercol’s “offshoring” efforts, these represented a big switch in approach. Until about

2005, the company had pursued a resolutely “do it yourself” stance, with little outsourcing. The philosophy had been

honed over decades and fitted in with its “handcrafted” image. It went as far as owning controlling shares in a

group of North American forestry businesses that supplied special cuts of hardwoods such as ash, beech and elm.

But this extreme “vertical integration” was both complex to manage – in around 2000 the company’s

4,000 furniture variants required to it make and assemble about 2,500 components – and it pushed up costs, putting

Ercol’s viability in doubt.

The business is still known for its classic chairs - products that have deep roots in Buckinghamshire furniture history

The business is still known for its classic chairs - products that have deep roots in Buckinghamshire furniture history

Ercol started its offshoring moves through agreements with contractors in Italy. This helped it to

introduce new products including bedroom furniture and fully upholstered armchairs and settees. Today, Ercol’s most

important offshore manufacturing partners are three Chinese companies and one in Turkey.

The offshoring policy has had to fit with Ercol’s approach to production, which emphasises the

flexibility to make a range of products and components. Behind this is a key characteristic that Ercol shares with

other other successful UK manufacturers: the ability to make a wide range of products in low volumes. Ercol’s range

includes about 350 models or designs across basic furniture types such as tables or sideboards. Counting

different timber colours and fabrics, there are thousands of variants, a huge number for a company with annual sales

of only about £20m.

The wide variety of parts and finished products the firm handles requires a sophisticated

production philosophy blending both modern automation and established craft techniques. Standard components such as

chair legs are turned out in Ercol’s UK factory in Princes Risborough in large numbers using computerised

machine tools. Other processes such as specialised wood bending (needed to create specific shapes of chair or sofa)

are also done at the plant but largely by hand in processes that have changed little in decades.

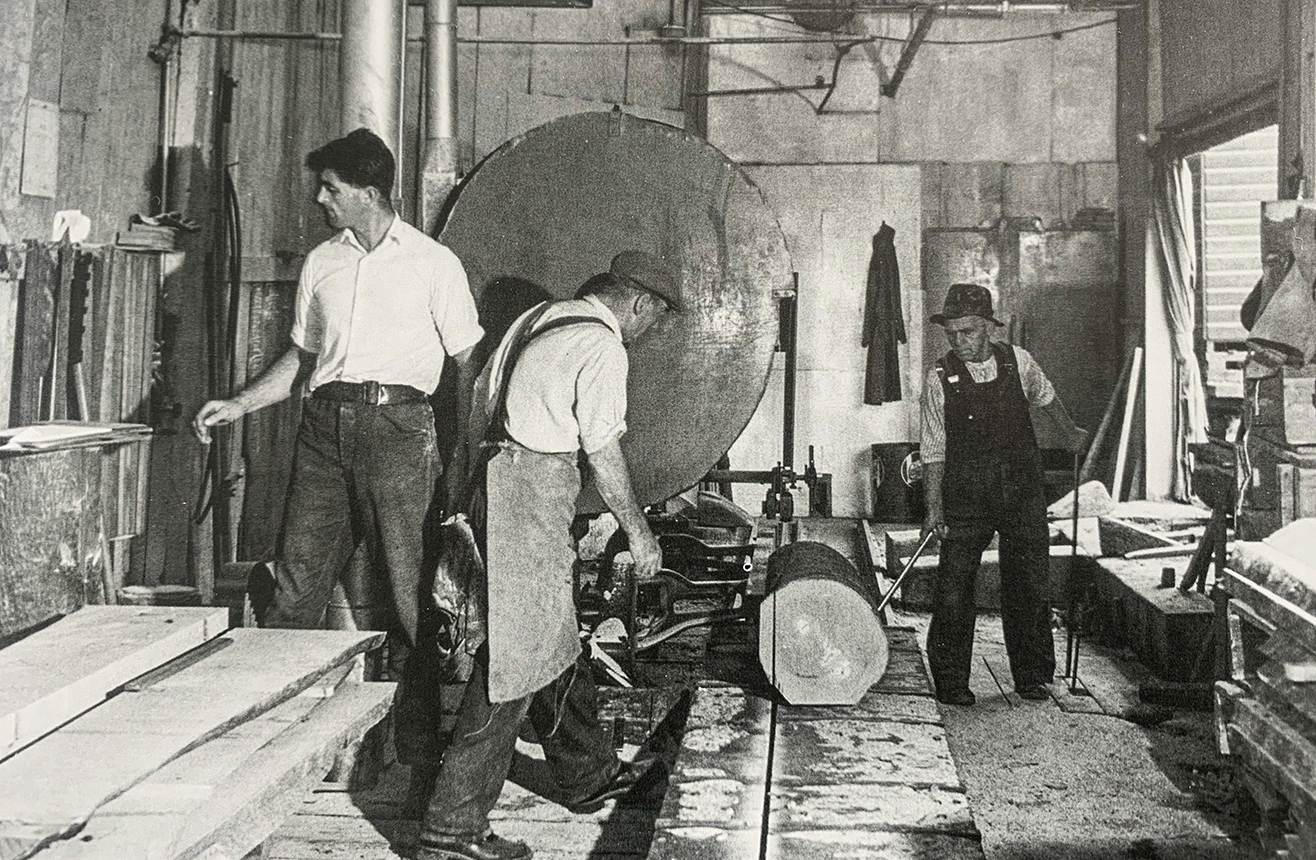

At one time, Ercol operated it's own saw mill

At one time, Ercol operated it's own saw mill

Overall staff numbers at Ercol have fallen considerably from a peak of about 650 in the 1990s. The

job losses are explained not just by higher productivity and the policy of offshoring some aspects of production but

also on decisions to leave some operations to external suppliers. For example, the company no longer operates its

own sawmill.

Rural town carves out a reputation

Ercol’s long links with High Wycombe, a small town in the Chiltern Hills near London, underlines

the area’s historical importance in furniture manufacturing. Due to the abundant wood from local forests, production

of furniture – especially chairs – took off in a big way during the 19th century. By 1875, an estimated 4,700 chairs

a day were being made in the Buckinghamshire town, with several hundred furniture makers in evidence.

Ercol’s founder, Lucian Ercolani, set up his company, originally called Furniture Industries, in

High Wycombe in 1920, after a spell in London learning about the furniture trade. He got to know two other

luminaries of the business –

Ebenezer Gomme, who had started his furniture company in High Wycombe in 1898, and Harry

Parker, part of the influential Parker family that was behind the famous Parker Knoll furniture band.

Ercol continued its association with the town until 2002 when it moved to a new factory in nearby

Princes Risborough, a key move in its plan to give itself a chance to prosper in the coming

decades.

Furniture for kitchens is part of the Ercol range

Furniture for kitchens is part of the Ercol range

Gomme’s company, meanwhile, had a large factory in High Wycombe until the early 1990s. The business

lives on today under the name G Plan, now based in Nottinghamshire where it concentrates on making upholstery-based

furniture such as settees and armchairs. Parker Knoll – which started life in London 1869 but had a factory in High

Wycombe from the 1920s – also continues to make upholstery products at a factory in Melksham, Wiltshire.

Both G Plan and Parker Knoll are owned by Sofa Brands International, a holding company for several furniture manufacturers. Other

well-known High Wycombe furniture names that are now gone include W.M.Birch, James Elliott & Sons and Joynson

Holland. However several smaller firms continue to make furniture in the town, including Greengate Furniture, William Hands

and Evans of High Wycombe.