A leading exporter of high-tech equipment says its operations risk being “strangled” by inconsistencies over government rules designed to control shipments of sensitive items that UK officials fear could end up in nuclear or biological weapons.

London-based Cryogenic makes powerful magnets and ultra-low temperature cooling systems of the sort that could in theory be used in weaponry and other military hardware, with specific concerns centred on China.

While the company says such anxieties are groundless, Cryogenic’s overseas sales have been severely disrupted by lengthy border delays, despite the company having had what it believes have been the necessary export clearances from the Department of Business and Trade (DBT).

Some futuristic weapons use magnets as part of their propulsion systems. The photo shows an experimental unmanned aircraft designed for hypersonic speeds and under development for the US Air Force

Some futuristic weapons use magnets as part of their propulsion systems. The photo shows an experimental unmanned aircraft designed for hypersonic speeds and under development for the US Air Force

The systems made by Cryogenic often end up inside equipment including particle accelerators and high-accuracy scientific instruments. Individual items can cost up to £500,000 and are used around the world in sectors such as materials research, medical equipment and particle physics. The company insists its products have no military application.

Jeremy Good, Cryogenic’s managing director, said: “We are concerned that unless we can find a remedy to the problem then much of our export business could be affected. Our business is being strangled and our relationships with customers, especially our main customers in Japan and elsewhere, are being stretched to breaking point.”

He adds: “There is no reason why any of our products should be embargoed because of concerns about military use.” Cryogenic employs 100 people and has a handful of competitors worldwide. Last year the company exported 97 per cent of its output, with nearly half of total revenues coming from Japan and China.

A key speciality for the company is making the systems needed to operate in extremely low temperatures, down to “absolute zero”, equivalent to minus 273° Celsius.

Hardware of this sort could – in theory – be used in the cooling systems for heat-seeking missiles and also for super-fast quantum computers that some believe could be applied by hostile powers in breaking top-secret military codes. High-power magnets related to those made by Cryogenic could have applications in a range of futuristic weaponry including space-based “rail guns” and hypersonic rockets.

At the heart of the issue is what appears to be a failure by border control officials at HM Revenue & Customs and counterparts at the DBT – who are responsible for export licences – to follow the same set of rules.

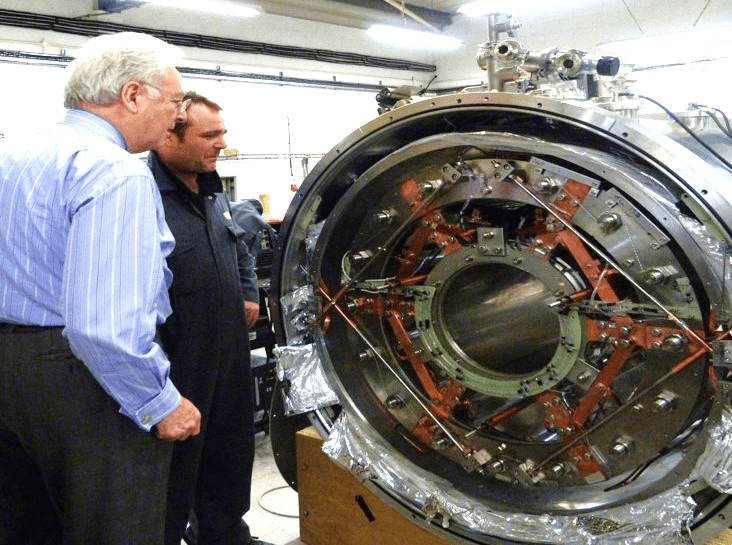

Jeremy Good, Cryogenic's managing director, pictured left, has been frustrated by what he says are government inconsistencies, but hopes for progress

Jeremy Good, Cryogenic's managing director, pictured left, has been frustrated by what he says are government inconsistencies, but hopes for progress

An admission by Lord Johnson – minister for investment at the DBT – suggests that border officials can “independently” stop shipments, irrespective of what has been agreed in other parts of government, including his own department.

Responding to queries from within parliament about the Cryogenic case, Lord Johnson wrote in an email in July that “the UK’s border agencies act independently on detainments [of goods] using their own information, though they will seek advice from across government in some cases”.

Good’s view on this point is that “it seems extraordinary that we have a government keen to promote growth, especially in export industries, but which can allow two government agencies that should work together not to do so”.

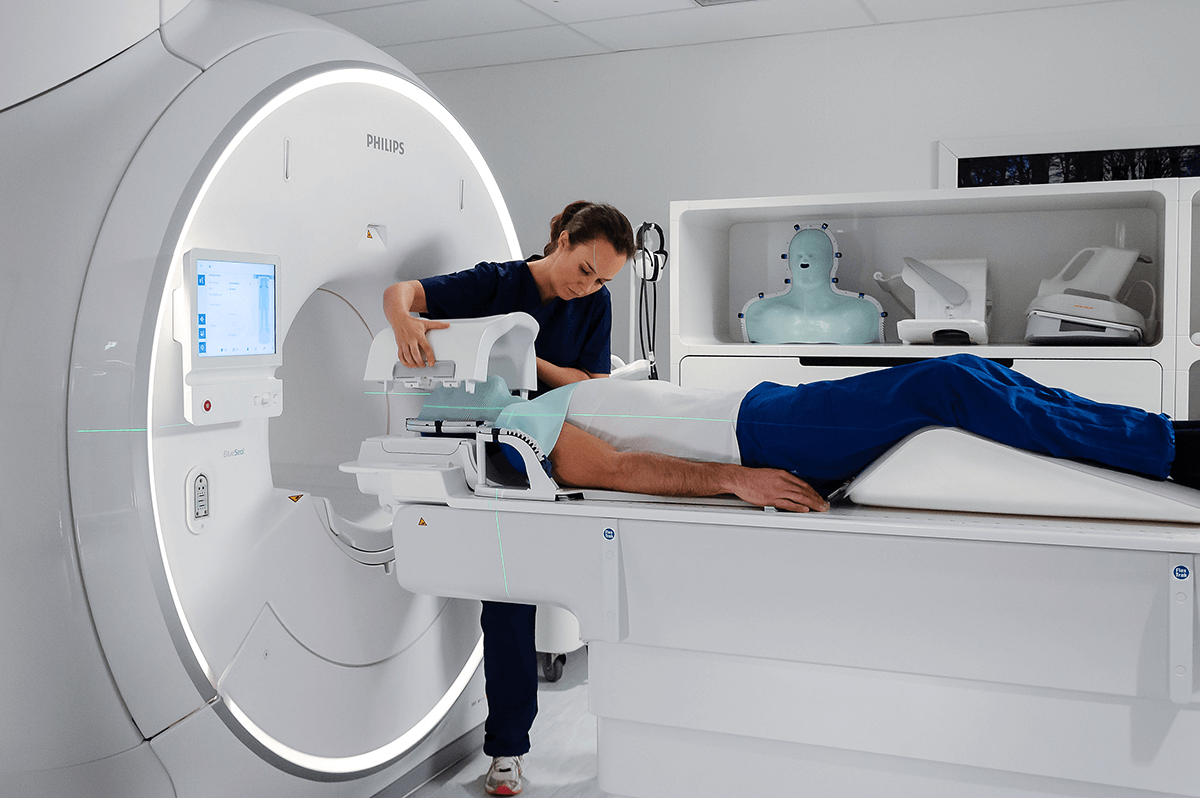

The company's equipment can form part of a range of scientific instruments

The company's equipment can form part of a range of scientific instruments

Good started Cryogenic – which in 2022/23 had sales of £15.8m – in 1992 after being involved with other high-tech businesses. In the past five years the company has spent nearly £2m improving its development and manufacturing operations at its HQ in west London.

Good’s frustrations are heightened by what he says have been his company’s efforts to check that its products due for shipment did not fall into the category of those barred for exporting. According to Good, on about eight occasions in the past year items exported by Cryogenic have been stopped at Heathrow by HMRC citing concerns about potential military use.

In all these cases, Cryogenic says it has either had the necessary export licences from the DBT or had been told by DBT that no licences were needed.

The bureaucratic tangle affecting Cryogenic has become harder to unravel following the tightening in May 2022 of UK rules over export of “dual use” equipment – hardware that could have civilian and military applications. Much of the concern has been linked to fears about the potential leakage of such technology to China, which has ramped up spending on its armed forces, triggering unease especially in the US.

The high power magnets made by Cryogenic are essential in some medical applications

The high power magnets made by Cryogenic are essential in some medical applications

In an email sent to Cryogenic in October about the halting of two shipments at Heathrow by HMRC, a DBT official said the government had “grounds for believing that the export is or may be intended, wholly or in part, to be used in connection with the development, production, handling, operation, maintenance, storage, detection, identification or dissemination of chemical, biological or nuclear weapons or the development, production, maintenance or storage of missiles capable of delivering such weapons”.

The two shipments were due to go initially to an equipment maker in Japan. After incorporation into high-specification machines called scanning tunnelling microscopes, the two sets of hardware had been intended for final delivery to customers in civilian research operations in Australia and Japan.

In emails sent to Cryogenic about a previous shipment, an HMRC official said that Good was in danger of offending against laws prohibiting shipment of sensitive goods. Such offences carried possible punishment of unlimited fine, together with imprisonment for up to 10 years. Good says he takes a dim view of this interpretation, as he had been exporting for more than 50 years with few problems until recently.

Neither the DBT nor HMRC wanted to comment directly on the Cryogenic case. The DBT said: “We take our export control responsibilities extremely seriously and operate one of the most robust and transparent export control regimes in the world. We carefully assess all licence applications from UK exporters and refuse or revoke licences when they don’t meet our strict criteria.”

HMRC declined to add to this statement. Officials from the two government departments met Good at the end of November. He said the meeting was “useful” and he hoped for progress to resolve the matter.