Airliner wings taking shape at big Airbus plant in North Wales: the aerospace sector is one of many that could

benefit from a comprehensive industrial strategy

Industrial strategy returns to centre stage

Stories in this series

Three former government business secretaries – one each from the Conservatives, Labour and Liberal Democrats –

lined up at the House of Commons recently to say why they thought a UK industrial strategy was necessary. “The

MPs found our views surprising,” the former LibDem leader Sir Vince Cable observed later. “What was interesting

was the three-way consensus.”

Whatever the views of the members of the House of Commons’ business and trade committee – who were also taking

evidence from the Labour stalwart Lord Peter Mandelson and the Conservatives’ Greg Clark – the chances are high

that Britain will introduce an industrial strategy over the next year or so. With a general election likely by

the end of 2024, Labour has a strong lead in the opinion polls. It has pledged to introduce a set of “strategic

priorities for...industrial policy” should it take office.

With an industrial strategy on the horizon after several years of vacillation on the issue by successive

Conservative administrations, Made Here Now is investigating the concept.

The first of three stories examines the recent history of ideas surrounding an industrial strategy. The second –

"Labour looks afresh at industry planning" looks at Labour’s thinking

on the topic, homing in on where manufacturing fits in with its

economic plans. Thirdly – in "New chance to boost high-growth

manufacturing" we consider the often-nebulous notion

of “advanced manufacturing”. What does this phrase mean? And once the term is defined, how can it best be

supported?

Apart from any change in political thinking at Westminster, many businesses view industrial policy favourably.

“Firms are clear that an industrial strategy would bring the benefits of a long-term vision and a stable

environment in which they can plan, invest and grow,” according to a

2023 report by the manufacturing group Make UK.

The Bessemer Society, representing mainly

small tech-based manufacturers, said this year:

“An industrialisation framework to complement the [UK] science and technology framework would enable priorities

and policies to be developed that turn R&D into market opportunity. A long-term industrial strategy, decoupled

from parliamentary cycles, would give clarity and confidence.”

Any UK move in this direction would fit into the international context. Industrial strategies are seeing greater

favour in many parts of the world, led by the US. President Joe Biden’s administration has pushed through the

CHIPS Act, which allocates $39 billion in government funding for domestic semiconductor manufacturing facilities

and billions more for semiconductor research and development. It has introduced the broader-reach Inflation

Reduction Act, supporting US manufacturing that has succeeded in tempting some European companies to relocate to

the US.

The car industry remains a strong part of UK manufacturing despite electrification challenges

The car industry remains a strong part of UK manufacturing despite electrification challenges

The European Union has announced a series of industry-based initiatives. Emmanuel Macron, France’s president,

has grandly declared (on behalf of the whole EU bloc) that "we [Europe] need more factories and fewer

dependencies". India and China have weighed in with their own ambitious programmes based on manufacturing and

advanced technologies.

In the UK, it seems that Labour’s current interest in industry strategy will result in at least a partial

throwback to 2008. It was then that Mandelson - as part of the Gordon Brown-led Labour administration –

brought the concept back into the mainstream after many years of rejection by the main political parties. Fresh

from a four-year spell in Brussels as European trade commissioner, Mandelson had learnt how different countries’

industry policies had a vital bearing on business performance. Brought back into office by Brown, Mandelson was

keen to introduce some of this thinking back home. While dismissing any suggestions of a return to the

interventionist approach of the 1970s, when the state ran large sectors of the economy and championed specific

British companies, Mandelson introduced the idea of an “activist” role for government in areas such as

technology, regulation, skills and investment.

A curious mixture of an intellectual and Machiavellian schemer, the Labour politician made a point of showing a

“strong and abiding commitment” to open economies and free markets. But a modern government should not shrink

from supporting sectors such as “green technology” and nuclear power. Such areas, he said, offered both high

growth and the creation of powerful mechanisms that the state could use to put the economy on a more robust

footing. If investment and market decisions were left purely to private capital, there was a chance the UK would

miss out. Without a broad-reaching strategy there was, he averred, a constant danger of governments creating new

policies on a piecemeal basis that were “insufficiently joined up and often overlapping”.

Despite Mandelson’s apparent devotion to industrial strategy, his party’s days in power were soon over. In the

2010 election Labour was swept away by the coalition Conservative/LibDem government. So Mandelson had little

time to embed his ideas into the UK’s industrial system, despite winning over to his ideas such powerful allies as Sir

John Rose, the hard-nosed chief executive of Rolls-Royce.

Mandelson’s legacy was, however, far from lost. Sir Vince Cable took on the mantle of industrial policy and

pushed it on. The former Shell oil company chief economist in 2010 became business secretary in the new

government. Helped by his own technocratic and logic-based mindset – arguably a useful set of skills for a

senior politician, but one which surprisingly few of them possess – he was given a largely free hand within the

Conservative-led administration. An industrial strategy – adapted from some of Mandelson’s beliefs but with many

stronger elements – was launched in 2012.

“It is generally better policy to have a framework, a strategy, rather than random interventions as arise, for

example, from government purchases of defence equipment,” Cable said.

“[There are] serious market failures in the provision of training, infrastructure, the “d” in research and

development and finance which the state needs to correct.” The government had a role as the “entrepreneurial

state”, he said, nurturing technology and management innovation. Cable won industry backing for useful projects

to back sectors such as automotive and aerospace and buttress UK-based supply chains.

Technology-intensive manufacturers could be assisted by greater government clarity over an industry vision -

particularly on issues such as skills

Technology-intensive manufacturers could be assisted by greater government clarity over an industry vision -

particularly on issues such as skills

Again, however, there was insufficient time to infuse this way of thinking into the foundations of government

policy. After the Conservatives formed their own administration from 2015 - without any need for support for

their former LibDem colleagues - Cable’s time at the top-level was dramatically ended. With his removal from

power, the concept of a vigorous industrial strategy for the UK became gradually downgraded. The Conservative

politician Greg Clark – a milder individual than either Mandelson or Cable and less of a political heavyweight

- served as business secretary from 2016 to 2019. But whatever plans he had for industrial policies were

barely encouraged by the rest of the Cabinet led by Theresa May. Ministers had other issues to struggle with,

not least the chaotic aftermath of the 2016 Brexit vote. Although the term “industrial strategy” featured in the

official name of the business department Clark headed, by the time his spell there ended, industrial strategy

had virtually disappeared from the agenda.

But the story does not end there. After several years on the fringe of top-level political deliberations,

industrial strategy looks like returning to centre stage. The next article looks at Labour’s approach to the

subject.

Labour looks afresh at industry planning

Labour politician Jonathan Reynolds (left) is the main architect of the party’s effort to devise a long term

strategy for business

Labour politician Jonathan Reynolds (left) is the main architect of the party’s effort to devise a long term

strategy for business

With the Labour party poised to adopt a far-reaching industrial strategy should it take over at the next

election, the key person in the discussion is Jonathan Reynolds, Labour’s thoughtful and well-regarded shadow

business secretary. Reynolds’ thinking on this issue takes in manufacturing and key technologies (which

traditionally have been at the heart of industrial strategy concepts) but also includes many areas of services

including those organised by government.

Reynolds provides useful clues to his approach in a 2022 policy paper. This says a Labour industrial strategy

will be centred on four broad goals or what he calls “missions”. They are: delivering clean power by 2030;

harnessing data for the public good; caring for the future; and building a more resilient economy. “These

missions are the strategic priorities for our industrial policy and setting them out provides a clear

signal and organising framework for business,” the policy paper says.

As to the different parts of the economy that Labour’s industrial strategy seeks to grapple with, Reynolds

chooses to divide these up in an unorthodox way. Rather than differentiating between sectors as is normally done

– by considering elements such as manufacturing, services and construction – Reynolds’ paper splits the

economy into four main parts or themes. Each of these can combine one or more of the traditional sectoral

slices. This way of looking at industry seems sensible. As his paper points out: “[The UK’s strengths] don’t

fall neatly into categories, with the realities of the modern economy meaning ‘intangible’ knowledge-intensive

services like design and analytics often combine and complement sectors like manufacturing.”

The first of Reynolds’ economic components defined in his paper is “sovereign capabilities”. These constitute

critical areas such as defence, health equipment and national telecoms networks. They can be regarded as vital

to underpinning the entire economy. The second encompasses “global champions” – areas such as parts of

chemicals or film making where the UK is a world leader. Third is “future successes” – “highly productive,

high-paying, export-intensive businesses that support well-paid jobs”. In this area, state involvement may be

needed to “lay the groundwork for innovation and exploration”. Finally, Reynolds has marked out what he calls

the “everyday economy”. This comprises activities such as leisure, and health and retail, which are the “the

sectors people interact with most in their daily lives and those that employ most people in the UK”.

Aerospace engine maker Rolls-Royce - along with many smaller firms - would welcome a stronger government lead on

a vision for industry

Aerospace engine maker Rolls-Royce - along with many smaller firms - would welcome a stronger government lead on

a vision for industry

In relating how these components could be assisted by a new type of thinking, Reynolds’ paper sums up:

“A modern industrial strategy should ...[look] across all parts of our economy and our country to assess where

support might be best targeted. While we want all businesses to have the opportunity to contribute to our

missions, we recognise that industrial strategy cannot focus equally on every sector of the economy. Alongside a

foundation of horizontal economic policies that will benefit businesses across the economy, we need to

understand the different types of vertical interventions that will be required to achieve our missions.”

While the paper provides a useful framework for assessing Labour’s likely stance, plenty of detail still needs

to be filled in. It seems likely that when the final elements of Labour’s strategy come together, it will

feature

within Reynolds’ current thinking six key principles that Made Here Now has been able to identify.

First is the need for governments to show a stronger broad appreciation of the role of

manufacturing,

acknowledging how boosting this activity can increase productivity and skills in the entire economy. Governments

must sharpen their definitions of what constitutes the key areas of manufacturing that require understanding and

support. The well-worn lists of so-called “advanced” or “emerging” manufacturing sectors should be looked at

afresh to define more closely which components are most crucial to future prosperity.

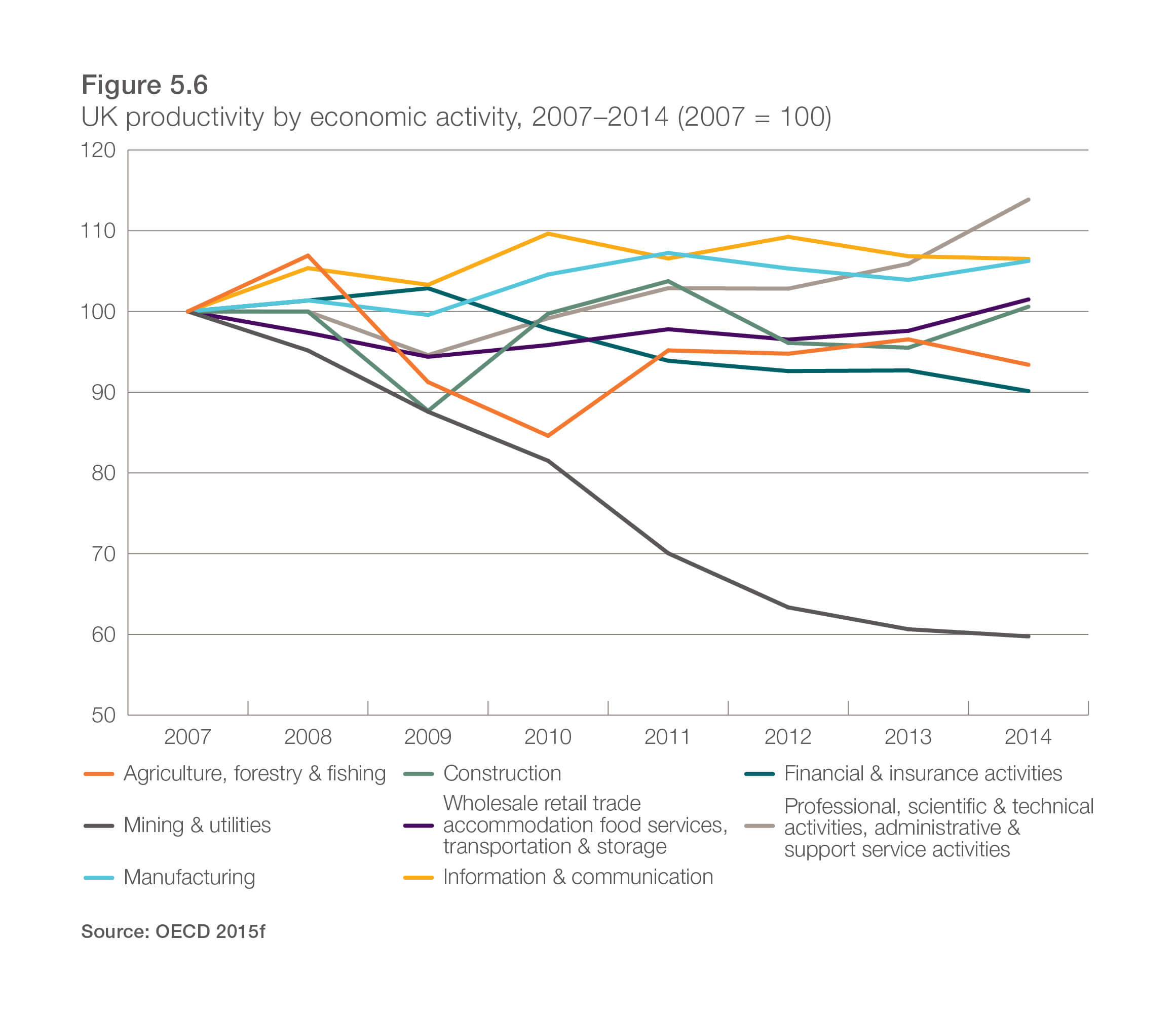

While the UK entertained two industrial strategies, from 2008 to 2014, productivity in manufacturing remained

flat. In 2024 it is little better: can a proper industrial strategy with +10 year commitments fix that?

While the UK entertained two industrial strategies, from 2008 to 2014, productivity in manufacturing remained

flat. In 2024 it is little better: can a proper industrial strategy with +10 year commitments fix that?

Second, policy should be based on shared ideas, with industry, academic and trade union

representatives involved

with designing and framing the specific measures that form part of the thinking.

Thirdly, there should be an

emphasis on “place”. Policies should be tailored to the needs of individual regions rather than being devised

centrally.

Fourth, “connectivity” seems likely to feature strongly. Thought must be applied to how the

various elements of

the industrial economy relate to each other. In this way, a set of measures aiding a company in one sector may

also have a positive impact on a business in an unrelated corner of the industrial spectrum and to which it

supplies components or services.

Manufacturing and services often connect. There are many examples of companies that combine both manufacturing

and services in a way that is both profitable and increases employment. Examples here include machine or

component producers that combine the service/manufacturing ethos by “bundling” into their product prices

packages a significant amount of service provision. It is this service – just as much as the “tangible�� or

product-based part of what the businesses are involved in – that can be vital to how the company helps its

customers. It can be the main reason customers choose to do business with it rather than a competitor.

Fifth, measures to counter the climate crisis will probably be a key part of the strategy,

featuring a mix of ideas ranging from ways to help businesses organise themselves better to combat the climate

emergency, to assisting over the creation of new low-carbon products or new power generating methods.

Sixth should be a focus not just on individual technologies that need support but on

“technology blending” – combining different technologies to create new services or products that are either new

or different. Important technical disciplines that should be included in this approach encompass the key areas

of automation and artificial intelligence, both of which have many potential applications throughout

manufacturing. Other technologies that can be integrated with others to powerful effect in new products and

related services include novel materials, engineering biology, and data transfer.

Enthusing young people about jobs in industry could play a big part in government strategies

Enthusing young people about jobs in industry could play a big part in government strategies

Reynolds and the rest of the Labour front-bench team probably have a few months to bring together the most

useful

ideas for a new-look industrial strategy. It seems they have made a useful start but still need to add some

vital elements.

It could be a good strategy to emulate some of the approaches that the former Liberal Democrat business

secretary

Sir Vince Cable – who has probably thought more about this subject than any other UK politician or industry

practitioner in recent years – sketched out in a policy paper as far back as 2012.

The UK needs, he said, “a clear, ambitious vision; the courage to take decisions that bear fruit over a long

period; openness to new opportunities as they develop; focus on the things we do best; and an enduring

commitment far beyond a five-year parliament or spending review period”.

Craft skills will continue to have a role in future manufacturing despite automation advances

Craft skills will continue to have a role in future manufacturing despite automation advances

If Labour can embed this way of thinking into the government machine – and, crucially, keep it there for a long

time – then it will have played a vital role in putting the economy into a better shape for the coming decades.

New chance to boost high-growth manufacturing

There is an obsession with “advanced manufacturing”. The next government needs to understand what it is

There is an obsession with “advanced manufacturing”. The next government needs to understand what it is

Advanced manufacturing is a term often used to denote parts of industrial production deemed to be high-tech,

fast-expanding, and worthy of government support. For all the ubiquity of the expression, efforts to understand

and explain advanced manufacturing have been inadequate. A chance to correct matters may come soon. Assuming the

Labour party wins power in the next election and introduces its own UK industrial strategy, it will be in a good

position both to unravel what advanced manufacturing means and promote it sensibly.

The role of manufacturing as a sector associated with high levels of productivity, wages and skills is already

well understood. Boosting the “advanced” part of the industry - especially as it encompasses many UK businesses

that are global leaders - therefore becomes attractive for any government keen to find growth levers.

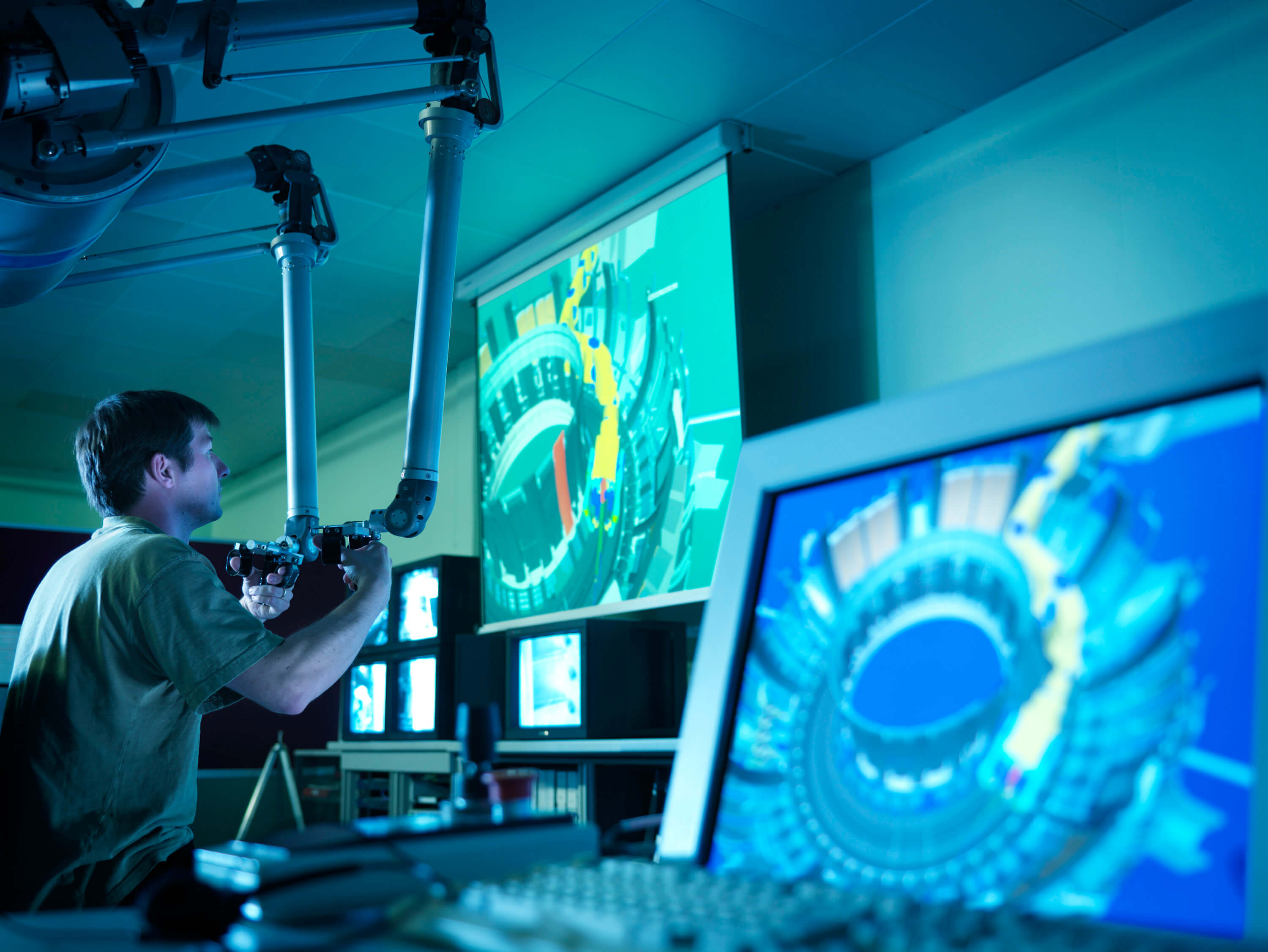

What is advanced manufacturing? Experts believe it is not only about machines, automation and software

What is advanced manufacturing? Experts believe it is not only about machines, automation and software

Rishi Sunak’s struggling Conservative administration chose to highlight this part of the economy recently. But

the “advanced manufacturing plan” published in November 2023 by the Department for Business and Trade was

disappointing.

The DBT defined the term as “production processes that integrate advanced science and technology, including

digital and automation, into manufacturing [helping] UK manufacturers create products that meet future

technological demands and enables the UK to lead on the twin transitions of net zero and digitalisation”.

The definition is too narrow. Novel science and technology can spur new ideas and result in powerful new

products. But non-technical ideas in management and organisation may also be instrumental in pushing a

manufacturer into the “advanced” part of the industry spectrum. Such management strategies include

choices over sectors of business to specialise in, groups of consumers or global regions to sell to, and how

best to integrate production and services. Even given the plan’s weak attempt at a definition, its efforts to

highlight the technologies important to advanced manufacturing – and which sectors are best poised to do well – suffers from flaws. Linked to the

plan was £4.5bn of government support over five years for a set of “strategic” sectors categorised as

industries where advanced manufacturing can flourish. They include automotive, aerospace, life sciences and

energy-related disciplines including offshore wind, carbon capture and nuclear.

While these are important, the list of sectors that can take advantage of advanced thinking in manufacturing is

much longer than the paper appears to recognise. Chemicals, industrial machines, instrumentation, and

non-automotive parts of land transportation (such as bicycles and mass transit) are just some of the other

sectors which contain examples of advanced manufacturers. It is important to recognise this.

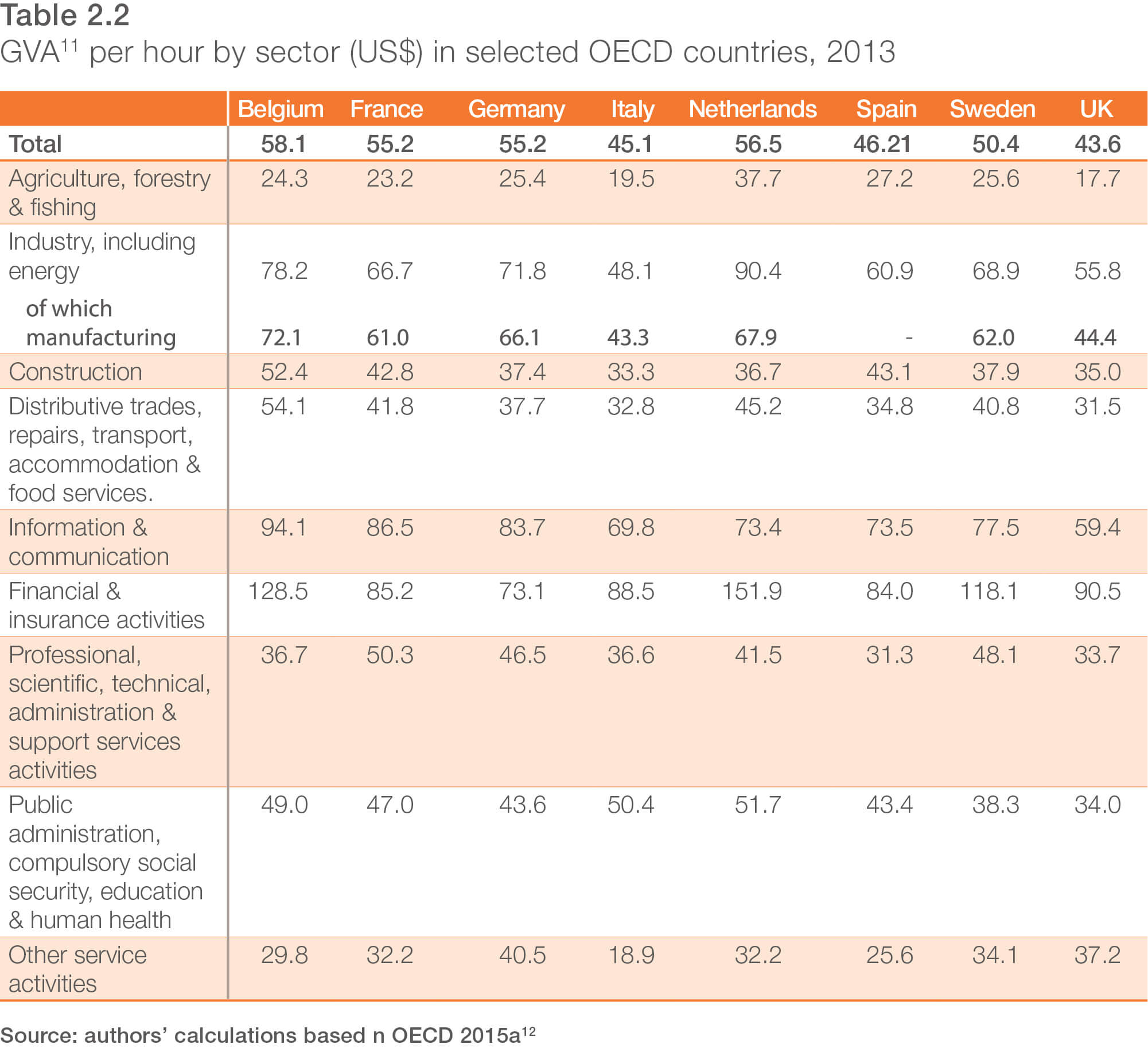

When the UK last had a formal industrial strategy, c. 2012-2015, its productivity was the lowest of eight

European nations bar Italy. It is not much better in 2024.

When the UK last had a formal industrial strategy, c. 2012-2015, its productivity was the lowest of eight

European nations bar Italy. It is not much better in 2024.

In its restrictive selection of industries and technologies, the advanced manufacturing plan follows a similar

line to other recent government expositions of key technical disciplines judged important to UK interests.

Pronouncements on the subject have tended to focus more on headline-grabbing areas deemed to be glamorous rather

than those that many industry practitioners would consider crucial. During the Liberal Democratic/Conservative

government, eight names were on a 2013 government list of technologies appropriate for support: “big data”,

space, robotics, synthetic biology, regenerative medicine, agri-science, advanced materials and energy.

Eight years later, a new government register of key technologies included just seven names. Of these, four –

synthetic biology, advanced materials, energy and robotics – had appeared on the earlier inventory, with the

addition of three new ones – electronics, quantum technology and artificial intelligence. By 2023, the special

technologies had been whittled down to just five, including quantum technology, artificial intelligence and

synthetic biology from the earlier lists, with the addition of semiconductors and telecoms.

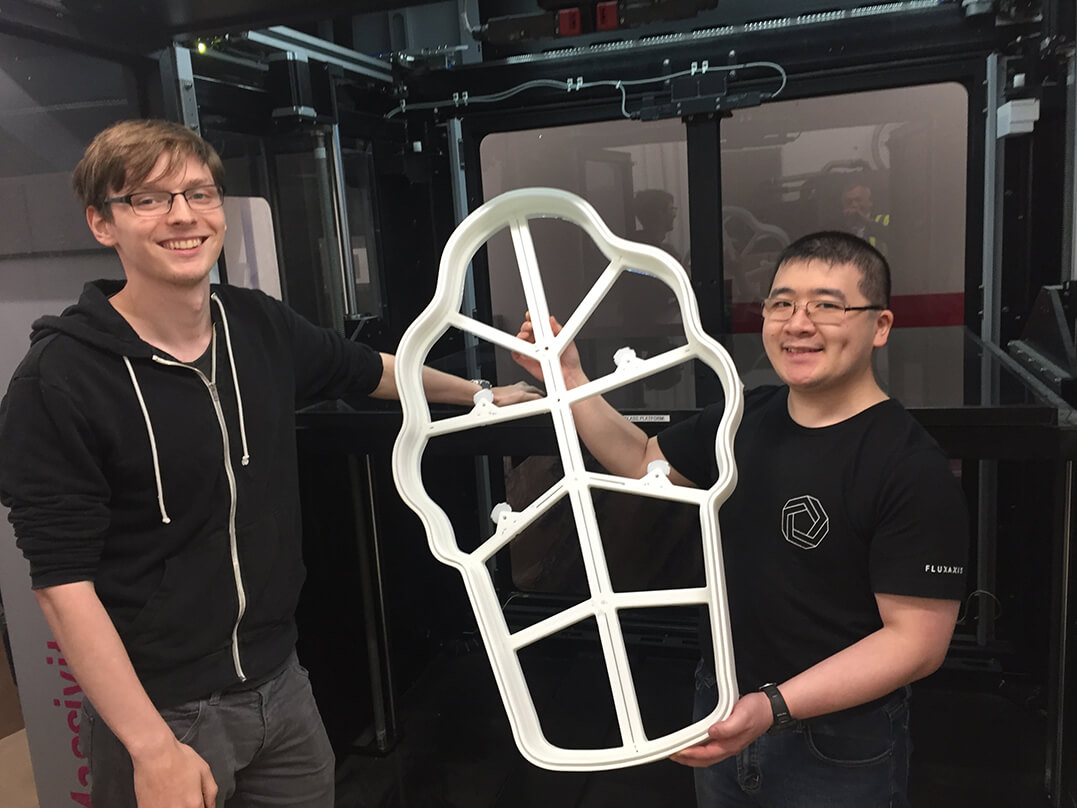

There is more government focus on skills needed for “high-tech” areas of manufacturing: AI coding, 3D printing,

and smart factory technologies

There is more government focus on skills needed for “high-tech” areas of manufacturing: AI coding, 3D printing,

and smart factory technologies

This partial view of what is important in technology has implications not just for manufacturing but other parts

of the economy reliant on scientific and technical skills. Commenting on the advanced manufacturing plan, Andrew

Churchill, chairman of aerospace parts manufacturer JJ Churchill, points to the document’s inattention to less

obviously seductive areas of technology such as welding. “The advanced manufacturing plan is silent on how these

‘low tech’ [employment] roles will be ….[addressed despite their importance] to the advanced sectors,” he says.

So given the shortcomings in current government thinking on advanced manufacturing, what might an incoming

Labour administration do?

First it would do well to define the term properly. A new government could adopt something close to the

terminology of a 2022 US government document. Advanced manufacturing is, says the US Office of Science and

Technology Policy,

“the innovation of improved methods for manufacturing existing products, and the production

of new products enabled by advanced technologies”

.

The explanation provides a commendably broad view, taking in both technology and organisation.

Secondly, Labour ministers and their officials could spell out not just the technologies that are fundamental to

advanced manufacturing but the organisational processes too. Here three ideas are crucial.

One is a focus on selling into “niche” areas with narrow parameters that can to a large degree be invented by

the

participating companies themselves, and to rely on selling services as well as products.

The best example here in the UK is the Formula 1 industry. This involves intensive use of engineering resources

to design and make high-grade machines that do little apart from playing the lead role in a global spectator

sport built on advertising. Another example is the UK’s Spirax Sarco, a big player in the narrow business of

steam-control equipment. Its range consists of 50,000 assorted items of pressure valves and regulators, sold to

100,000 customers.

A second important element is the ability to devise solutions to business problems. The approach is often geared

to making products as highly customised “one-offs”, and to the needs of a single customer rather than many.

A third key organisational factor is the facility to excel in a range of technical disciplines – which will

probably include information technology and automation but also less obvious areas such as materials and design

– and find the common ground between them.

Brompton Bicycle and Renishaw – leaders in folding bikes and measuring instruments respectively, and Made Here

Now sponsors – have both achieved consistent success in part through following this approach. But given the UK’s

narrow official way of regarding advanced manufacturing, both companies would probably struggle to be recognised

in government circles as exemplars.

The third thing a Labour administration might want to do as it looks afresh at advanced manufacturing is to make

a decent estimate of how much of the economy this sector represents. Rough calculations based on the criteria

spelled out in this article indicate that advanced manufacturing perhaps amounts to about half manufacturing

output, so accounting for roughly five per cent of the economy. But a more precise evaluation is needed.

Given the strong role of manufacturing generally in nurturing growth, the advanced part of this sector is worth

boosting in whatever way a government thinks – or can be shown – is desirable. How it does this is up to the

politicians. Before this can be done it is vital to understand advanced manufacturing correctly and sweep away

the half-baked assessments of the past. There must be a strong hope that – assuming Labour forms the next

government – it will do a better job on this than the current one.